- Home

- Tracy O'Neill

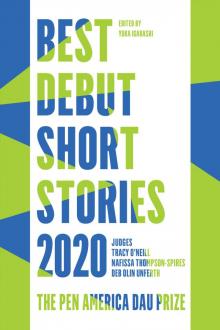

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Page 11

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Read online

Page 11

“The doctor gave me something,” I said.

She rolled her eyes. “He gave me the pamphlets, too, Will.”

“Maybe when we’re back in Milwaukee we should see about getting you some help.”

It wasn’t what I’d wanted to say.

“You think I’m crazy,” she whispered.

“No, baby, no.”

“Of course you do.”

She pushed me back on the bed and her towel fell away. She took off all my clothes and kissed me so her tongue touched my tonsils.

“This is it, right?”

I wanted to say no, no, it’s not, but it would have been a lie and when I smelled the place behind her ear I was so hard I said nothing at all. It had been months. She worked her tongue all the way down my chest and stomach and when she took my dick in her mouth, I wanted badly to be inside her or at least to touch her or smell her, but she stayed down there with her hips over my knees and one hand on my balls until I almost came, and then she bit down on me and I cried out and flipped her onto her back. I drove myself down into her throat, and I knew she couldn’t breathe, and I put my hand on her neck and felt myself there, and when I came she reached up and put her fingers in my mouth and pulled me down to her, and I kissed her so I tasted myself, and I licked her lips for her. I tried to touch her, to open her legs gently, but she swatted me away and closed her eyes. I fell asleep fast.

I woke to a cry that did not belong to Tess. The door to the bathroom was open just a crack, and a slice of harsh fluorescence shone onto the bed and my body. I got up and watched Alice through the crack, one leg up on the sink, her back curved, her feet arched, one hand between her legs. I pushed the door open and she sank down onto both feet and turned toward me.

“What are you doing?”

Her face was flushed; she was still naked, her hair hanging around her shoulders. I imagined putting my hands in it. Maybe I wanted more. Maybe I wanted too much. I went to her. She put her hand up to stop me.

“I want to make you come,” I told her.

“I can’t.”

“Please.”

She lifted herself up and sat on the edge of the sink. And I went to her, put one hand behind her head and touched the insides of her thighs with the back of the other. I got down on my knees and pushed her legs apart. Her vagina was still split with a dilapidated railroad of black stitches: the places where the dissolving threads had gone in and out of the skin were red and white and sticky with something that didn’t smell like her at all. I turned away, and hated myself for it.

She grabbed my head and pulled it back, pointed at the stretch of stitches still left, a second angry mouth, and said, “You did this to me.”

Willa C. Richards is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she was a Truman Capote Fellow. Her debut novel, The Comfort of Monsters, is forthcoming with Harper (2021).

EDITOR’S NOTE

When I think about what it means for The Rumpus to be a home for “stories that build bridges, tear down walls, and speak to power,” I think of Kristen Sahaana Surya’s “Gauri Kalyanam.” Surya weaves a tale that feels timeless and timely, foreign and familiar, artful and effortless all at once. From its first sentence—“Her heartbeat is a history folded into a vessel.”—“Gauri Kalyanam” engages readers with its beautiful language and exquisite storytelling. Rather than moralizing or preaching, Surya utilizes craft and story to impart important, universal truths about gender inequality and patriarchy.

Kristen Sahaana Surya’s poetic voice sings on the page, and I’m thrilled this artful, wise story will be celebrated as a PEN America/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize winner. I have no doubt that Surya is an emerging talent to be reckoned with, and we’re proud to have given her first published piece a home at The Rumpus.

Marisa Siegel, Editor in Chief

The Rumpus

GAURI KALYANAM

Kristen Sahaana Surya

HER HEARTBEAT IS a history folded into a vessel. When she is born her mother counts three beats where two should sound: an arrhythmic omen embedded in a baby’s chest. She is born black, not brown, and on her first full moon she is offered the sweet-sounding titles of fair-skinned goddesses. Her mother smells her skin in kisses and calls to her: Papa, my Papa, Chinna Papa, Kutty Papa, my darling baby girl. When she is still small her mother rubs her with turmeric powder and coconut oil, callused hands stroking soft skin, until her body buzzes with the softness and the brightness of a woman whose existence depends on erasure. Her mother’s hands snap chicken necks, pound rice, and pull her hair. Her mother’s hands hold the cash that comes in her dowry, tie the collar of the cow in their yard, and slap her face a thousand times to rid it of its ugliness. Her mother’s hands are bilingual: to her face, which they seize and smack and spit, they are hammers against nails; but to her hair, which they comb and braid softly before bed, they are the amma whose eyes refuse to meet her own.

She is sold to a man twelve years her senior.

She is sold with the promise of cash and a cow.

On the day of her wedding her heart beats twice.

HER HUSBAND IS called Vasu and he carries the face of a bull. He is wider than she expects, but also taller, and a gash sits square in the seat of his chin. A round ring of plated gold hangs from the sliver of flesh between his nostrils. Red, infected, and oozing, it clanks against her teeth as he pushes into her hips at night. He does not drink or smoke or gamble. He does not wash his mouth or clean his teeth or kiss her in the dark.

She spends her days reading filmi magazines that she pulls from the next-door neighbor’s trash. In the evenings, she prepares dishes she knows he will eat without complaint. When he relishes a meal, he eats in thick silence marred only by the steady smacking of his lips. When the food does not suit his taste, he asks her where she learned her cooking, and laughs before she can answer.

“I knew you were a good woman when your father told me you stopped school in the third standard,” he says often. “Good women learn when to stop learning.”

Before the monsoons they go to the movies. He takes her to see Singari at the theater behind their house one night, where he buys red-buttered masala popcorn and holds her limp fingers in his wide hand.

“Padmini is the greatest actress of our time,” she tells him as they sit, “but you can still hear her accent when she speaks Tamil.”

“Too many movies will make you lazy,” he says.

She does not take any of his popcorn.

When the movie is over, he takes her to a newsstand outside the theater and points to a magazine with Padmini’s face.

“If I buy you this,” he asks, lilting his voice toward her with the promise of affection, “will you enjoy the pictures?”

She takes it from his hand and pretends she cannot read the title.

But he is sweet sometimes, too, sweet-speaking and eyes dancing with yearning looks. His house is her first home without a mother, and in the night when she uncoils her hair, it is he who sits behind her with a comb, murmuring soft stories in her ears as he layers her hair in threes. He pins her plait with fresh flowers and inhales near her neck as if he is making a memory.

When life swells in her belly she dreams of Yashoda. She envisions peacock-blue babies born with the power to suckle the breasts of demons. She dreams of a son born to strangle snakes made of men, of a daughter born to stamp the earth open and accept a woman whole into its womb. The midwife comes and she spreads her legs and pushes pain into personhood.

Her son is born black, not blue, and when he wails he is handed to her, bloody sac streaming and white cord uncut. She holds her boy in her elbow and studies the wholeness of him. Two arms, two legs, black hair, one mother. She runs her finger against his gums and sees the whole world sitting in the center of his mouth. There it all sits: blue sea and sky, green earth and soil, fabled myth and man, swirled into a globe at the base of his throat. How vast it was, the whole wide world around them: hung idly between teeth and tongue, caugh

t or carefully kept in the crevices of a toddler’s gums.

HERE IS THE history she cannot ignore: her first tooth fell when Vasu began to hit her.

First on the back of her neck, so that no one would see, and then, next, when the sights and sounds of her battered body could no longer bother him, her face, and then the cigarettes, whose burns trailed the length of her arms like a lover’s lost kisses. Papa, Baby, he called her, like everyone else, but she found herself hunching tightly over their children—two sons, now—as they suckled her breasts, as if she were a wall. Not soft or pink or sweet, like the gums his fists had left behind, but a solid steel tooth in her own right. Twenty-three years young: toothless, fearless Papa.

He himself is not fearless, and when the walls within her rise she watches his hurricane melt. He runs his thumbs across her cheekbones. He begs to hold her child.

She studies her sons for signs of the bull within them. When they are still small, her mother tells her, they will crawl and hit and hurt each other. This is the male nature, to hurt, but you are their amma and you will soften them with your woman ways.

But they are bubbly balloons, colorful fat candies stuffed with laughter and sweetness and good-smelling hair. She cuddles them close and covers her bruises. She runs her finger across their tiny teeth at night, covering them with fluoride and sweet dreams. Vasu buys them gold chains and used books and bright colored balls. When their eyes grow wide with fear, he hides his fists, sets them into his pockets until she is in the bath or the bedroom, until they are alone and the children are sleeping. He pounds her face into dry cement. She does not scream. Her eyes search the drawer of her dowry.

She begins to count the cash she came with.

“HER NAME IS Madhavi,” Vasu says.

Madhavi stands behind her husband in the doorway. She is small and black-haired and red-eyed, and when Papa speaks she looks at her feet.

“Yes, that’s all fine,” she says. “Who is she?”

Vasu holds Madhavi’s hand in his and brings her to his left side and says, “She is my wife. She is to be my wife.”

“And who am I?” Papa asks him.

“You are my first wife,” he says, reaching his right hand toward her. “You are a good woman and my first wife and you will learn to love Madhavi as I have learned to love you.”

“And who am I?” she asks him again. “Who do you think I am?”

DEPARTURE LOSES ITS question mark. Satchel bags quickly stuffed with coins and cash, babies clinging to her neck, she flies into the warm night, the sounds of Vasu’s snores trailing behind her.

After they leave him they find a yellowed straw hut. They are lucky to have it, yes, because while the hut itself is barely a hut, thatched roof and tarp door, they are still together: Baby and her babies, cooking chicken on an open flame and waiting in paranoid peace for him to come and collect.

Her eldest watches her while she sleeps. She feels his eyes boring into the bony shoulder under her sari. He is a young man, nearly six years old, and soon she will have to buy clothes for him. His penis protrudes when he walks, strutting around the house like a rooster claiming his roost.

“If he comes here,” her son tells her, “if he comes here, let me handle things.”

His brother is too young for him to hold, but he is still the man of the hut and the least she can do is to let him think it.

She wonders what work can be done with her body. The women in the huts adjacent see her scars and slip her cash; when she refuses, they call their boss.

“We can’t sell sex without teeth,” he declares, “but her legs are firm and we need laborers.”

In the mornings, the lady laborers tie cotton cloths around the width of their heads to better balance beams and bricks against their skulls. The beams are heavy stone and Papa cannot lift them with her arms alone, but she holds them high against her towel, slipping slightly in the wobble of her chin and the shake of her shin against her babies’ pulling palms. She is paid twelve rupees a day for her service, or so she is told—she does not count the cash.

Men wander from hut to hut during the dusty break hour, searching for food and conversation and company. She is grateful for the screaming children, for the bright toothless smile she must offer them.

“Amma,” the men call her, an unfamiliar ring of respect denting their hoarse voices, “Mother, thanks for the meal.”

They bring her rice, squirreled or stolen from somewhere, and bright pull toys for the children. They address her eldest as a man. They leave her clothes untouched.

In the evenings, she squats in circles with the beam balancers and the hut dwellers, slapping wet turmeric into each other’s skin to stop the darkening. There is a cool feeling against her dry joints and a warm feeling in her chest. The younger girls have a secret hope of lightening their complexion, and she tells them again and again and again that it will work, that there will be a handsome hero at the end of the film, that bright skin and a sweet smile will somehow send them soaring.

The house that she is building has eight bedrooms and a veranda. She studies the blueprints with the wary, wishing eyes of a woman whose hopes have never been granted.

“I will have a house like this one day,” she says to the other women, as if it is a joke.

“You and what husband, Papa?” they ask her. “Who will buy this house for you?”

“I will buy two,” she says.

The palm who pays her grabs her wrist. It is the forceful grab of a startled man who has only just been bothered, or the desperate grab of a man who has only just begun wanting.

She clangs her coins against his jaw, silver clashing against his small white teeth. She pushes his face away with her open palm. Her stomach is clenching. She tells him to let go, or perhaps she does not—she cannot hear herself over the thick cloud of her fear.

The scars on her arm bore holes into his eyes. His face carries the freshly stung sadness of disappointment, and she sees that he is staring at the burns on her arm, at the scars on her shoulder, at the pinkness of her smile.

“I am sorry,” he says, eyeing the children clinging to her sari.

“I am not,” she tells him.

He opens his wallet. “Take something.”

She shakes her head. “Work, yes. Not money. Not money only.”

He narrows his eyes as he thinks. “Housework?” he asks. “My wife needs help at home.”

She asks how many bricks she will have to carry.

“No bricks,” he promises, “only babies, Papamma.”

And then she is Baby and Mother together, past and present welded to one.

THE PAYROLL OFFICER lives in Adyar, one hour from the hut by public transit bus, so she straps the children to her back and to her front. They climb aboard, bodies packed tight in stinking heat and sweat, unwashed men gazing at the small curve of her breasts. Their dark faces flicker into Vasu’s—the bright gold of his ring sinking out of their nostrils—but when she smiles at them, toothless and leering, she sees their faces flinching and feels freedom flying in her belly.

The children she cares for are sullen and stubborn, ignoring her sons and her endless offers to prepare sweets.

“Tell us a story,” they demand, and when she has run the reams of births and deaths dry, has told every trial of every god, she asks if they have yet heard the story of Devadasu and Parvati.

“No?” she asks, etching incredulity into the curves of her mouth. “First,” she says, “think of a dark theater, and when the screen turns light, Savitri is sitting in the royal court . . .”

There are months. Papamma makes magic out of movies and feels tension building in her belly. She hears from a cousin of their old neighbor that Vasu is searching, that he is angry, that he wants his children.

“Keep them close, Papamma” the women whisper. “He can find you with his eyes closed.”

She sees him slipping through the doors of huts in the deep black of night, and balancing beams across his head with the women

in the mornings. She sees him selling fruit and milking cows, teaching maths to her children, and stitching saris at the tailor. She sees him married to Madhavi and tied, too, to the hundreds of women in the huts who look like her.

“Rest easy,” her neighbors tell her, “if he comes here, he will have to come through us.”

Her sons wrestle with sleep, bulls charging through their dreams, and in the dark dank of the hut she cannot soothe them.

“He will come to the school,” she warns them when they wake. “He will try to give you money, he will try to take you away.” Do not leave me, she thinks, but she does not say it, because it cannot leave her lips and it does not need to be spoken.

When he comes for her, he is quiet and final.

He waits at the bus stop in Adyar. His shirt is full of soot and his hair is caked with dust.

“How did you find me?” she asks. “How did you come here?”

“What’s one neighborhood,” he says, “what’s two when there is love at the other end?” His voice is freshly churned butter hanging high on a pot. “Come home,” he asks her. The weight of the question is caught between them.

“Home is not your house.”

“Madhavi misses you,” he says, in the wheedling way of yearning for truth in his own lies. “I miss our sons, and she misses her sister.”

“Sister?” she says. “Leave me. Leave my children be. Leave me, leave me.”

“You will come,” he insists, and he reaches for her arm.

Best Debut Short Stories 2020

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Quotients

Quotients