- Home

- Tracy O'Neill

Quotients Page 2

Quotients Read online

Page 2

“The official stories are insulting. Were they that insulting when it was us keeping them?” he said finally.

“Everyone has secrets,” Jeremy said, “especially a country.”

“But the world was more spread out then,” Wright said.

At the end of when Wright and Jordan were Wilmington and Allsworth, they had flamed out of the army’s Intelligence Corps the way that either you decided was part of the job or that made you ask for a new name. When he’d first been recruited to Operation Banner, the Intelligence Corps mission in Northern Ireland, Jeremy had known only the outlines, that the Provisional Irish Republican Army had taken up terror in the name of a united Ireland, and loyalist paramilitary groups like the Ulster Defence Association and the Ulster Volunteer Force responded in kind, and neither the police in the Royal Ulster Constabulary nor the British Army had been able to stop the violence. At the end, he did not know much more. People with access to high grades of classified materials manufactured credentials and rerouted them to other professions. Now Wright taught courses on the philosophy of the mind and the philosophy of language at King’s College London, where probably there were other men who needed aliases, but all the while into the rest of their lives after Northern Ireland, it was Jeremy and Wright who on occasion met. They found shadows slanted across corners. They whispered, something centripetal leaning them toward each other, spinning, circling on snippets, rumors.

Wright’s assumption: there were current intel guys tracking him. His former employer would want to make sure secrets stayed. And so together was the only place they allowed the rage to express on their bodies since duty. The world was deadly, and they were pretending to be gentle men.

“I remember once One Rock telling me about when he was a young handler.” Jeremy leaned back into a chair. “He was telling me the problem was the route to Mecca. Arab nationalists in Aden. The National Liberation Front blew up a party at the home of a Foreign Office official. It had seemed so quaint. So far away and ancient.”

“MI5 wants to distinguish geometry now,” Wright said. “Self-starting rumors they stopped trailing Khan and Tanweer because the two were merely ‘on the periphery’ of another operation.”

“When there is no periphery to terror.”

“It promises death anywhere.”

Jeremy watched Wright pour another drink. Drink it. Pour another. He could sense the risky nostalgia in the room, in Wright musing that there would have been a trail of transmissions to follow, A to B, B to C, C to D, D for direction. Intercept the signals of the Underground Attackers, he was saying. Semper vigiles. Someone had told someone: it’s time. Time to make the most private thing a person could ever do, dying, a public event. And MI5 had permitted it to happen.

“We have to realize what’s not ours anymore,” said Jeremy. “We did what we could.”

Wright stood. “Don’t treat me like one of your call center sobbers. If it were over, you wouldn’t be here.” He crossed his arms. “Bastards waited for the G8 Summit.”

“Because Blair would be away at Gleneagles.”

“Because drop panic in the center,” Wright continued. “Watch the ripples. All the eight go home unadjourned by terror. Might’ve been UK news. But now it’s worldwide. They’ve scaled down the globe with perfect timing.”

“At Gleneagles they were meant to pool terrorist data,” Jeremy said.

Wright wrung his lips into a tight coil. “These bombers have mastered their irony.”

Mastery. Irony. The drink organized Jeremy’s hands in the shape of the glass. Steady. “Thomas shouldn’t have known,” he said. “Why credit default right then?”

Usually, it was he counseling Wright against big picture theories, what the opposition was doing, who was the object of extinction. Wright collected news clippings. He was certain the story wasn’t the story when it was official. He did not know the ops, but he knew there were leaks. Wright obsessed over who had circulated dossiers when they were handlers. Over splinter groups. Over elections. Jeremy would say you could go crazy worrying about strangers in Belfast, Sudan, the Balkans. There were too many people you didn’t know. So you recognized your finitude. You did not clarify the codes. You went on eating breakfast, popping sleeping pills. You could suffer more for the remote suffering, or you could realize your business wasn’t the public good anymore. It was one day, yours, at a time. He would say those things before Alexandra.

“Thomas, he’s just part of a trend. They believe all those triple-A CDOs can collect interest free of loss, that the CDP will earn out eventually. Simple as go bullish, go bearish, go to the country home.”

“I know how it works,” Jeremy said. “I’m the one hedging.”

And yet.

During the anthrax panic, Strategic had maneuvered the long and short game on Bayer and a handful of generic drug companies. Though the patent had expired in nearly every country, Bayer still held the patent for Cipro, a drug used to treat anthrax, in America. In the midst of an ally emergency, Strategic made an inconceivable dump of capital.

“I’m quitting.”

“And just say you’re right,” Wright said.

“I am right.”

“Just say you are. What is the use of the walk away?”

“The away,” Jeremy said. “It is a good quality to be in the circumstances.”

“Can’t get away from what’s inside you.”

“What’s inside?”

“The listening, the half-breath.”

But for now, the strategy: Continue the image, especially to her. Continue the regular fictions of the person he was supposed to be. He was supposed to be someone nonchalant in love and lies, someone who quipped and would never tell Alexandra he preferred her to food and water. “Three weeks earlier, I’d have said nothing.”

“But it wasn’t three weeks earlier.”

“It was right before the bombs,” Jeremy said.

An angle of the chin. A tunneling with the eyes. It was not pity exactly, Jeremy knew, but the look dropped down a shaft of silence between them, a punctuation mark in the face. Wright recrossed his arms, a reversal of right and left. He worked his tongue over his upper teeth, and finally he spoke.

“Ring the prepaid if you want to talk,” Wright said.

Then he stood up and walked, and Jeremy followed. The lines of the hallway seemed almost to choreograph his exit. They did not shake hands. It was simpler, the gesture. Not even a sigh, and Wright opened the door out into the London fog for Jeremy to fade back to the theater of his new life.

Chapter 5

Alexandra wanted to be wry and knowing, like the women in New York who somehow had it all, calm and casual in their thin cashmere sweaters, buttering bread for their children at brunch on the weekend and stepping crisply to hail a cab from work at five, and all of it, their happiness, ignored like a given. There was an unfeathered romance to these women, how normalized the abundant life was to them. But it was abashing a little, the big weather of feeling for him. At night Jeremy Jordan astonished her body, his much stronger than the drawn face and lean legs would suggest, a thin man but sprawling, with all that warmth rising off him. He was capable of reminding her how wide his shoulders were as they blotted out the cool cast of the moon in the window. The rage of his rising and falling matched her own; they knew each other then as they couldn’t in words.

In his apartment in Islington, they lay looking at each other side by side with the tips of their fingers just touching on one side of a breath, pulling apart on the other, a sort of stretching come from their lungs. The voice of someone famous reached from another room. A newsperson.

“But you love your job,” Alexandra said. “You obsess over it.”

“I am preoccupied by it,” he said.

“I think the word for it is occupied,” she said. “You are occupied. That’s what an occupation does.”

>

“I want to do something valuable,” he said, “instead of lucrative.”

“You could do both,” she teased, “be a regular George Soros.”

“And break the Bank of England?”

“A humble man would allow that perhaps in his hypothetical second career he would only cause the market to tank occasionally, but you, you must be the architect of national economic crisis.”

“In my hypothetical second career, I will not settle for less than disaster,” he said. “I will know my worth.”

She could see he did not want to think for a while. He moved his hands into her hair, and then her shirt, pants. She spread out on the bed. When he collected the bone of her pelvis in his hands, she closed her eyes and there was depth in the darkness. “Look at me,” he said, and she watched his eyes grow closer to something like alarm. What it is: tiny tilts, shifts, but the objects, views, fell off, and then she heard something her own, plaintive and undemanding, an unresigned sigh, and there were no qualifications between them.

Or else, there was only one irking detail, one marring absence. But that could change. She believed that. Change, after all, was what she had done with herself. She had not wanted to be a persuaded woman, so she entered a field where she could prevail upon. And when that didn’t work, there was standing in proximity to the best people she could find, the ones who would not make a fool of her suggestibility. Genevieve Bailey. Lyle Michaels. Jeremy.

And perhaps, after all, soon she’d hear from Ray Gutierrez. Ray Gutierrez was supposed to be a man with an affinity for minutiae. Ray Gutierrez was supposed to be a man whose expertise was searching—better: a man whose expertise was finding. Ray Gutierrez’s secretary had said he would know how to locate loopholes in the vastness of the planet to find her man.

There was still a flush in her body. She moved a box of roses from the bedside table so that it rested between them, ripped a petal off and rubbed it against her cheek. “Poor Gavin will be inconsolable when he hears you’ve left Strategic, you know.”

“Gavin?”

“Thomas,” she said. “Gavin Thomas. Called me yesterday with a referral. It seems he’s got some developer friends with skin in the game for a Belfast makeover.”

Jeremy’s voice was sharp, right-angled and boxy. “And what would Gavin want with Belfast?”

Chapter 6

Alexandra thought of telling Jeremy, so she did not tell Jeremy when Ray Gutierrez called to accept her case. She knew it was only the urge to deposit some of the unseemly, febrile nerve knocked through her. The irony, of course, was she would have told Shel if what she had to tell wasn’t that she was seeking him.

Because Shel was a person who had shared whispers with her. They had whispered to hold out the loud pronouncements: who they were, what was wrong. They had known what people said about them and their church bin clothes, what people said about their mother. But in whispers they had had a secret from their mother and from everyone else, and it was that they were better people than they looked, that when one day they left that place, and they would, they would, they would be even better, alchemized.

There was combustion to his talk, punk rock. He burned up with shunting past idols. But, too, sometimes she would, when they were young, see her brother across a way asking the direction to a store or if he could sit down, and though he was the older, an awful tenderness colonized her in the tectonics of his face altering, surprised to be the recipient of kindness, decency. It was never something she could have mentioned, but she wanted to be someone in his life who made him less surprised by the absence of malice.

It was this thought, this hope, that had made her a little short of breath on the call. Alexandra’s cheeks—she had felt the pink on them. “Remind me how long since he disappeared?” Ray Gutierrez had asked.

“He didn’t disappear,” Alexandra said. “He is simply appearing where I don’t expect.”

And so she had continued. She had more to tell, and Ray Gutierrez listening nearly forgave something of the past, made it sit differently. She was involved in the process of finding. Ray Gutierrez was. And as a result she would not need to think every time news broke, a shooting, a terrorist attack, that if Shel had been there, she’d never know. She could imagine a family again, and she could remember that Shel had once told her bad luck did not run in sprees.

Chapter 7

Jeremy had selected the time and place, and now, across from the restaurant, at the settled hour, his view telescoped toward Lawrence, formerly of 12 Intelligence Company. Lawrence was seated at a circular table with embroidered flowers falling down its sides, a heavy tumbler to his right, and a menu beneath his forearm, and even at a distance, Jeremy could see that in the twelve years since they’d last seen each other, Lawrence had become a composed man. He ordered a pint, wore a smart tan suit, and he didn’t lean over the table. The one remaining tic was a triple-blink every so often.

He had been the one person left Jeremy could think to call.

Casual gait—an aspiration for his entrance.

When Lawrence stood for Jeremy, they shook hands. Firm grip, dry. Left hands grabbing shoulders. It was all very brisk, and they exclaimed over lengths, over how long it had been. “My girlfriend speaks very highly of the firm,” Jeremy said. “She’s with Orbet.”

“A good account,” Lawrence said, unrolling cutlery from a cloth napkin.

They sat across from each other with their menus opened in angles. Jeremy had already decided what he would order but moved his eyes down the lunch selections anyway, did not glance up a few beats before saying, “So you’re properly private now.”

“There is money there. Executives want to know if such and such Russian oligarch is only a local gangster or ambitiously criminal before the handshake. And you?”

“I’m weighing my options.”

A man came to their table to take their orders. Lunch salads. Clean. Light. And of course, in preparation, Jeremy had already eaten.

“You were always good with computers,” he said when the waiter left. “We didn’t realize the applications then.”

“You mean you didn’t,” Lawrence pipped. “I always knew. I was saying, what are these researchers up to?”

“You were prescient.”

“No,” Lawrence said. “I was paying attention to what was happening right then in the present.”

“And you’re married now?”

“Lydia,” Lawrence said. “She’s a nurse, so she says she doesn’t need children. Every adult is a child in the hospital.”

“Does that suit you?” Jeremy asked.

“I have clients. Every adult is a child in business.”

For a while, they spoke of the Olympic construction through the city, and they spoke of Lydia, of Alexandra, places to holiday. Their salads came, and Lawrence requested another beer. There was a song leaking through the restaurant.

“Was surprised to hear from you,” Lawrence said. “Most people come to Tyle before a hire, not after.”

Jeremy shifted his weight in his seat, moved his arms to resettle the shoulders of his jacket. “I was curious.”

“But you’re not in craft anymore.”

“I’m not in craft. I have a life worth keeping as it is.”

“And this has nothing to do,” Lawrence ventured.

Jeremy furrowed his brow. He shook his head. Control the flow of knowledge. Quarantine. Distribute. He had missed the signs at Strategic. Now there was cordoning off signs of his own.

“Because some of us,” Lawrence said.

“Not me,” Jeremy said.

For a while in the barracks of Lisburn, just beyond Belfast, he had been pleased to notice something choral was happening to him. When it had begun he didn’t know. One day it was simply that he noticed himself thinking, and all of what he thought had once been directives delivered to him, thoughts that mea

nt he could sense himself spin backward, reporting from the future his adherence to command. Telling his commanding officer, One Rock. Telling Wilmington. Actions tailored to the telling. Objective: live up to the correct story. He couldn’t distinguish instructions from his own watery mind, and he had thought it made him stronger. His feet planted and the advice became him, sank deep into his guts like it had always been a part of his makeup, so that when he looked in the mirror, he did not see the occasional stammerer, pink-faced and apologetic, but a man who handled, a man who was not afraid.

He had been wrong to not be afraid.

And so now, he looked at his plate as it was set down, the long fingers of rocket snarled around each other, green and dressed in lemon. The tuna was clumped on top of slim stalks of asparagus, and there were hard-boiled eggs split open, the yolk audacious and staring. He cleared his throat. “You know, once One Rock told me something.”

“There’s a classy man. Never coughed on a cigar. Never coughed period. And of course, always in his whiskey just one rock, at the barracks pub.”

“Clockwork.”

“He was decent, and he was dignified. I never knew anything about him.”

“No one did,” Jeremy said.

Lawrence’s eyelids flapped, quick as insect wings. “So One Rock,” he said.

“It was early in my tour,” Jeremy began. “I didn’t know what he wanted to tell me. If I was in trouble, if I was to be promoted. I went in, and I’ll never forget it. He told me, ‘Sometimes what we see, the psychologists call it countertransference. The analyst projects wishes, hopes, desires on the patient. Handlers and informants, analysts and patients. Seeking love, seeking truth, maybe, but often, most often, what we see is a desire for closure. Neat plots.’”

Lawrence worried a mole at the edge of his chin with one finger, head tilted. This feature was one Jeremy had never before noticed.

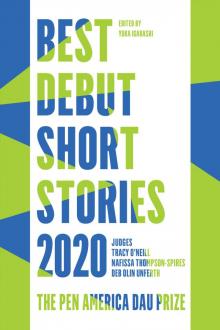

Best Debut Short Stories 2020

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Quotients

Quotients