- Home

- Tracy O'Neill

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Page 16

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Read online

Page 16

Madam draws a deep breath. “I see. Thank you, Cephas.”

She goes inside, slamming the door so hard the windows rattle. Next, the shouting starts. I hear only Madam’s voice; it seems the sister used up her shouting batteries while attacking Elina. I draw closer to the veranda, the better to hear through the open windows. Madam rants about the smoking and drinking and spoiled-brat routine.

“When are you going to grow up? You’re over thirty, an old woman. Time to act your age. And let me catch you harassing my staff again, you will see my bad side. You will see it,” says Madam. The next second, two packs of cigarettes fly out the window. “Smoke out there before you kill us all, for goodness’ sake!”

Iye. I never knew Madam had such a temper. I leave, before she catches me eavesdropping and shows me her bad side.

CHIPO DOESN’T HAVE the brazier going when I arrive home today. Her supply of bananas and roasted peanuts is spoiling, she says. We eat the blackened bananas and stale peanuts, slapping at the mosquitoes that needle our arms and legs. Across the road, one of the children is crying and calling to his grandmother.

“Ambuya, Ambuya. Wake up!”

I glance at Chipo, the food somehow now tasting too spoiled to swallow. Ambuya has seemed a little older of late, a lot more tired. She breaks rocks with a hammer by the side of the road, selling the resulting stones to those people building houses. It’s not easy work for an elderly lady.

“Someone should check on her,” says Chipo.

I don’t want to be the one to do it. One of our older neighbors, silently volunteering, goes into Ambuya’s darkened house. The crying stops. Soon, the grandchildren scamper out, coming straight to Chipo. She croons and rocks them, and takes them into our room when the neighbor comes out of Ambuya’s house, asking someone to fetch the police.

OUR ROW OF houses collects some money. It’s not much, but it will hold things together until Ambuya’s son arrives from the Copperbelt tomorrow. Us neighbors and Ambuya’s friends from church gather at her house: the men on the veranda, the women inside. The grandchildren cling to Chipo, and the green smell clings to all of us. It’s getting worse. It always gets worse just before an outbreak of something deadly. Some of the mourners are whispering that the cholera’s back.

“That’s how it starts,” they say, “with the old women and the babies.”

At times like this, I’d like a big car like Madam’s so that I could drive away and leave the network of green streams behind forever. Leave the crowded streets and noisy taverns and corner street vendors and their credit chickens. Leave, like my brother Patrick did. He lives in a yard bigger than Madam’s. A yard with only one house, not a cluster of houses. His guard works only for him, not for three other households.

I huddle closer to the brazier and hold out my hands to the warmth, even though I’m not particularly cold. I got better grades than Patrick; I could’ve gone to university, too. But I wanted money now-now. So I found work as a security guard. Patrick went to university and was broke for four years. He’s not broke now. Patrick doesn’t get chicken on credit and can afford to buy his wife ten Brazilians.

“CEPHAS, WHERE HAVE you been for the past two days?”

“Sorry, Madam. I had a funeral. My grandmother died.” It’s kind of true. Ambuya was everyone’s grandmother.

“Oh.” Madam’s frown dissolves. “My condolences. But please next time phone or send word.”

“Yes, Madam.”

She takes a few notes out of her purse, gives them to me, and for a moment her hand hovers like she’s going to pat my shoulder in some cringe-making gesture of sympathy. Thankfully she reconsiders, and I escape to open the gate. Elina’s been watching the awkward exchange from the veranda. She makes a clicking sound in her throat, mild disapproval, and goes back to applying polish on the veranda floor.

“What’s your problem, you?” I ask, keeping a few steps away from the veranda. The polish smells like industrial-grade paraffin, makes me queasy.

“Your grandmother died a long time ago, iwe, Cephas. Lying is a sin, ka. Sinner man.”

“Yes, keep talking. Keep annoying me. I’ll call the sister to come and shut you up.”

Elina laughs, completely recovered from the drama, it seems. “Ya, ya, ya. She’s mad, that one. Ati contact lens. A blue one, for that matter. Do I look like someone who’s got time for blue eyes?”

I’d like to stand around laughing with Elina, but the work has mounted during my two days away. Leaves to rake, lawn to water, trellis to trim. It’s afternoon before I get around to tackling the trellis in the back garden. The heat is like a blanket wrapped around me, humid, suffocating. I’d like a glass of ice water. I’d like a cold shower. What I get is the sting of sweat in my eyes and sunburn on the back of my neck. I hack at the honeysuckle, vicious like I’m stabbing a witch. Quite by accident, my gaze wanders to the window of the room where I brought the sister’s bags weeks ago.

I stop hacking.

She’s asleep, her face turned away from the open window. On the pillow beside her is the Brazilian. A wig. Not a weave. The sister’s own hair is done up in intricate cornrows as thin as a needle, nice enough. But the prize, the bonus, is that length of silk three times my wages and Chipo’s combined. Madam’s sister is from London: she’s rich. She can easily buy another wig. A man like me, on the other hand, I’ll never get another chance to give my beautiful Chipo this one thing she desires; a thing she deserves.

I reach through the window.

Madam’s sister keeps sleeping.

I grab the thing and go back to work with it tucked under my shirt. It’s insanely hot work, hacking at a honeysuckle bush with a full head of hair nestled against your chest.

ONCE AGAIN, CHIPO doesn’t have food going when I get home but instead sits on a little wooden stool next to the lifeless brazier. There’s mealie-meal and kapenta in the house, cooking oil, onions, tomatoes. Why hasn’t she cooked?

“Why haven’t you cooked?” I ask, my plan to whip out her present from under my shirt on hold.

Chipo stares at the house across the street. It’s lively again with the noise of a new family moving in. On the veranda, a woman threatens to smack a girl who’s dancing around a blazing brazier with a sizzling pan on it.

“The Copperbelt uncle took Ambuya’s bed and table,” says Chipo. “He left the boys. They cried and cried.”

This sometimes happens. Property grabbed, children abandoned. I lean back against the wall, scratching an itchy spot on my belly under the wig.

“Where are they now?”

“Ambuya’s church friend took them to the school,” says Chipo.

An orphanage in the community. “They’ll be all right there. We can go see them sometime.”

Not looking at all convinced, she stands up and turns her back on the happy family across the street. “I’ll prepare you some food.”

Chipo’s voice is dull, her shoulders slumped.

I touch her cheek to stop her from going inside, and say, “It’s okay, we’ll eat at the tavern. Madam gave me some money.”

Interest sparks in her eyes. “Really?”

“Yes, really.” I pull the wig from its hiding place. “She also gave me this. Why don’t you go and bathe, then put it on?”

Chipo clutches the wig, strokes it, laughs, high-pitched. “Brazilian? Oh, Cephas! Thank you, thank you.”

At the tavern, Chipo tosses her head and runs her fingers through her hair, and makes sure her friends get a feel of it to verify it’s the real thing. I’m content to watch her being so happy. We eat nshima and T-bone steak, and drink all the money Madam gave me, and dance to the latest tunes, Chipo preening like the most beautiful peacock that ever lived.

LATE TO WORK, bleary-eyed, head pounding. Madam’s also late for work, I notice. Her car’s still parked in its usual place. I doze while watering the grass under the jacaranda tree. The tiny flowers on the lawn are brown, sad and withered, purple no more. Elina leaves the veranda to com

e and talk to me. I can guess what she’s going to say.

“Madam’s sister has lost her wig. Imagine.”

I try to act surprised. It’s not easy. “Lost her wig? But how?”

“Who knows? She’s always drunk; she could’ve left it anywhere.” Elina darts a glance at the living room windows, lowers her voice. “She hasn’t stopped crying about it. Real tears.”

“Is that why Madam hasn’t gone to work, because of the crying?” I ask.

“Over a silly wig. Some people.”

We both shut our mouths when Madam’s sister storms out onto the veranda. Barefoot, her clothing wine-stained. She lights a cigarette and paces; she puffs and paces. Yelling at Madam through the window in between puffs. She has recharged her shouting batteries, definitely.

“Don’t you get it? How thick are you? I can’t go back. I have no papers. What you see on me, and in those suitcases, it’s all I have. It’s everything. It’s ten years of my life. Just a wig?” She laughs, hysteria in her voice. “You have no idea how tough it really is.”

“What’s she talking about?” whispers Elina.

I shrug. “I don’t know. Some newspapers?”

I do know that Madam’s sister can’t shout forever. Still, I block out her yelling, and water the plants, rake the lawn. Count down the hours till I can go home and rest my pounding head.

Mbozi Haimbe was born and raised in Lusaka, Zambia. She writes African-inspired realist and speculative fiction. Mbozi completed a Master of Studies in Creative Writing at the University of Cambridge in 2018 and is currently working on her debut novel. “Madam’s Sister” was a regional winner of the Commonwealth Short Story Prize in 2019. Mbozi is a social worker and lives in Norfolk, England, with her family.

EDITOR’S NOTE

“Don’t Go to Strangers” is rare for its depth and humanity, and demonstrates formidable powers of both observation and, just as essential, empathy. Matthew Jeffrey Vegari traces the intricate nuances of not one but two marriages, and the slippery tensions, sorrows, and unexpected passions among those four characters. The point of view moves gracefully from one character to the next, while the scope is contained to one late, intoxicated evening. Through that focused lens, the reader gets a panoramic overview that is nevertheless intimate in its observation. The exquisitely developed interiority of all four characters, whose competing (if unspoken) needs bring them inevitably, though subtly, into conflict, generates the narrative’s quiet tension. There is, for each protagonist, the ache of a loss, a worry, a vulnerability, or an unmet desire they carry through their days. It’s the precision and tenderness with which Vegari renders those aches that makes this piece memorable.

It was an easy editorial decision to accept this story, and we were proud to see Matthew Jeffrey Vegari join the illustrious roster of writers whose first professional publication was in ZYZZYVA.

Laura Cogan, Editor

ZYZZYVA

DON’T GO TO STRANGERS

Matthew Jeffrey Vegari

IN THE LIVING room, two couples sit on opposite leather couches, one hand-in-hand, fingers laced around fingers, the other slightly apart, shoe heels touching on the shag carpet below. Another dinner party of friends and coworkers has ended, and the couples carry on even as they begin to forget their words. The women finish off tall glasses of champagne; the men gulp down warm bottles of beer. It is after ten. Everyone has gone home for the evening, with the exception of Alice and Trevor Jackson, who do not overstay their welcome. On the contrary, the hosts, Allen and Jane Mitchell, are pleased to have friends linger behind. Between the marriages of the Jacksons and Mitchells there are three girls and a boy, two children per couple, who are upstairs sleeping in the case of the Mitchells, or, for the Jacksons, a few miles east, watching a movie with a babysitter who has been told that things could end at any hour.

Allen Mitchell takes a final sip of his beer and squeezes his wife’s hand. It has been a long day for them both, and now they can relax and enjoy a drink or two, maybe a slice of cake. They worked hard to entertain twenty people in their home, and things went well—very well, in fact. The guests arrived on time; dinner was served without complaint; the thunderstorm, once predicted to ruin the evening, postponed itself for another day. Allen looks across the room to Trevor, who is telling a story about two of his students, one he has told before, about a spontaneous wrestling match. Allen appreciates that his friend of many years can enjoy this night with him. He has known Trevor through their graduations, high school and college, and their weddings, and tonight the celebration of his own promotion registers another victory. In a way, he thinks, they are like brothers. He has seen Trevor grow from a young boy with a thin frame to a towering man, a father, with large arms and a sizeable stomach. And, much like brothers, their relationship has changed over time, too. Last week, after discussing Trevor’s upcoming thirty-sixth birthday over lunch, he became conscious of a pause in their conversation—a lull—as the two of them looked out the window and chewed their sandwiches. He found comfort in the familiarity of their friendship, a friendship that eliminated the need to say anything at all. The silence itself was full.

Jane laughs at Trevor’s story, one that gets funnier each time he tells it. She looks from Trevor to Alice, who grins uncomfortably, perhaps worried that her husband’s old joke will fall flat. Jane is not fond of Alice Jackson but appreciates how her own husband gets along with Trevor. Trevor is taller than Allen, better at sports, the one prone to overdrinking at gatherings like this. Allen is smarter and handsomer, his hair showing no signs of thinning. Trevor is a gym teacher and Allen is, now, a vice president. Unlike the two men, however, Jane and Alice do not complement each other. Their friendship was not formed organically, and instead they met out of an expectation for spouses. As she knows many people do, Jane maintains her friendship with Alice out of convenience: for the sake of their husbands, it is simply easier to be friends than adversaries. Not for the first time this evening, she wonders what a man like Trevor sees in a woman like Alice, a woman whose nose bends at the tip and whose cheeks engulf her small eyes. She is a good mother, Jane thinks, but a hostile woman.

Allen removes his hand from Jane’s manicured fingers and secures two more beers from the outdoor cooler. Under the white container lid, the bottles float in tepid water, their labels peeling off like dead skin. He searches for lime wedges and grows frustrated in the dim light. He turns and knocks on the window, but Jane calls out and shakes her head, pointing across the house. The limes are in the kitchen—he is too lazy to retrieve them. Trevor won’t mind. Allen closes the door to the patio and re-enters the house, watching a few moths flutter to the light fixture above. Even when they leave the screen door closed, the moths find their way inside. His wife is right: if the bugs will intrude regardless, better to remove the wire mesh entirely. It is ugly.

Alice tacitly agrees to stay late so that her husband can have a good time. He works hard, and, unlike her, has only one close friend in Allen. Trevor is introverted until he drinks, so she takes it upon herself to find new restaurants and outings when things get slow. There are a few reservations and parties lined up in the coming weeks, but the Mitchells are their closest friends. Alice doesn’t like Jane, but company is company. Like her, Jane is an only child, and both their fathers have died. There is some comfort in their histories, though not much else. Alice is unyielding, hardworking, disciplined. Jane is carefree, less organized, and equally happy. For their husbands, they sometimes meet for walks and always exchange gifts on birthdays.

“Wouldn’t you rather go on a nice vacation once or twice a year,” Jane asks, twirling the stem of her champagne glass, “than buy a cabin—a cabin!—that doesn’t let you go anywhere else and forces you to spend money on repairs and upkeep?”

Alice looks at her watch, a Timex purchased on sale. She realizes that Allen must have gotten a fairly big raise at work. She wonders what it means to go from regional manager to vice president. She dislikes the Mitchells

for this arrogance; it was typical of them to make it hard to say congratulations. Allen may have been promoted, but nothing fundamental has changed. Tonight is business as usual for the Mitchells as they brag of their own successes and prevent the nice evening from speaking for itself.

“Wouldn’t you rather go,” Jane continues, “to Paris, London, Tokyo?”

Alice wants to reply with the frankness that a question like that deserves: of course she’d rather travel! Of course she’d rather have a cabin in the woods! For her and her husband, it isn’t a matter of preference. It is a matter of having the opportunity for preference. But, to at once challenge Jane and keep up their façade, she tells her that she’d rather have a cabin. Because if the Mitchells invited them for a weekend, they would be able to go. She thinks to add that they should make sure to have a guest bedroom, but that’s a little on the nose. Besides, she doesn’t actually want to go on vacation with the Mitchells.

Allen decides not to hold Jane’s hand when he sits back down. She brought up the new house even though he told her to wait for another night. He genuinely wants to know the Jacksons’ opinion, but this is too much. They held a dinner party to celebrate, and his wife just gave away the extent of his new salary. It’s a significant raise but not an unexpected one. His boss told him to be proud of the promotion, of the achievement. To mark the occasion more permanently, he already bought a new grill, a Weber, the expensive kind with six burners. He understands that a second house is so much more than a grill, almost like having another child. He can see Alice growing uncomfortable. He spies the straightening of her spine, the smoothing of her dress across her lap.

Jane doesn’t know why she brought up the new house. She often compares drinking to getting in the pool: she’s cold for a moment and then warm all over. She admits that she shouldn’t have said anything, and that Allen specifically warned her of this, but Alice was sitting there, smugly, making her silent criticisms. Soon, Jane knows, Alice will make a comment that provokes them all. So there is something satisfying about a preemptive strike, about flipping the script, even if it is too easy, even if tomorrow she will regret embarrassing herself. She can never point to the exact moment in the night when Alice spoils the fun, but like the light outside, there is a slow change in color, from a warm yellow to a cold black, until the only sources of light are the individual flashes from fireflies: Trevor, Allen, and her. And though she doesn’t know how it got to be so dark, she knows who is responsible.

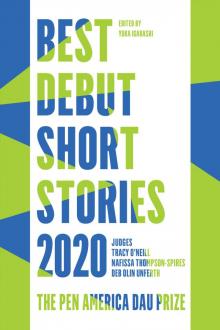

Best Debut Short Stories 2020

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Quotients

Quotients