- Home

- Tracy O'Neill

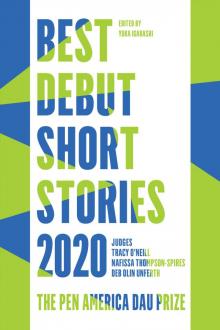

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Page 17

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Read online

Page 17

Trevor is surprised by his happiness for Allen. On some level, he feels that he, too, has been given a promotion, though on what merit he can’t say. Maybe for being a good friend. Maybe for pretending that he doesn’t know his wife hates the Mitchells. Alice says she hates Jane only because of her coyness, but he knows the truth: his wife hates the successes of others. Hate, he realizes, is too strong a word, but he likes to deal in extremes. It is why he always drinks too much, works too hard, angers too easily; why he was the best linebacker in high school and college, while simultaneously at risk for losing his scholarship; why he has only one very good friend.

“We were discussing, you know, the issue again last week,” Alice says, placing her hand on her husband’s leg and noticing the tiniest stain just below his knee.

“Babe, not now,” Trevor says. “And it’s not an ‘issue.’”

“No, no. I want to know what they think. What do you think now about us having another baby?”

“Well,” says Jane.

“Oh,” says Allen.

Jane wants to know why she has had this conversation three times in two years. Twice on Alice’s birthday and once on a dinner date. There is no more she can say, but so much more she feels she must: Alice and Trevor do not have enough money; their marriage seems just stable enough to maintain the status quo; their two kids will be out of the house in fewer than ten years. Why would they start over now? Deep down, she knows that this has nothing to do with children. For Alice, children, and any other topic pulled from an imaginary catalogue she might call “Family,” are but an excuse to have a conversation with others, a dialogue so that she feels present and acknowledged. Jane’s mother, a psychiatrist, told her so during a visit a few months ago. Her mother has many theories about many people but this one is particularly insightful. Jane has mentioned this to Allen in passing only once, worried that her mother will come across worse than Alice. Tomorrow—and she hopes she will remember the precise way to say it—her husband will learn more of what she really thinks of Alice Jackson. She will say that Alice ruins these dinners with her questions, suffocating conversation with a thick blanket of too-personal topics, all under the guise of lighthearted intimacy. She will try to speak without hyperbole, to restrain herself as best she can, out of respect for Trevor. But Alice has embarrassed herself tonight, far more than her own comment, however calculated, about a new house. Alice talks as though her family inhabits a filing cabinet, color-coded by age and sex. These are not issues for the company of others. They are issues for—a therapist.

Allen makes an effort not to look amused, taking as many sips of his beer as he can manage. Trevor, he now remembers, warned him on a recent run that Alice might make a fool of herself: “When she asks, if she asks, say something about the kids being out of the house in a few years. Don’t mention money. Never mention that.” Allen promised that he would toe the party line. He thinks the Jacksons certainly could have another baby, but something has stayed with him since that conversation. He was sure he heard a tremor in his friend’s voice, one that betrayed a great resistance to the notion of renewed parenthood. It was an almost biological response, and if Trevor had not already had two children, Allen would question his ability to conceive at all. Trevor had once been so adamant about having kids, about becoming a dad. Allen knows these ongoing troubles stem from a common source: the Jackson marriage, two people deeply at odds with each other. Through his wife, he has learned that Alice is happy as a mother, content with the ordinariness of her life and reluctantly accepting of the ordinariness of her partner. But Trevor, living under the same roof, seems caught in a long-lived jet lag, fatigued by something without remedy. “A kid can’t solve problems,” Trevor told him. “It only adds more.”

Trevor feels himself loosening up, caring a little less about his wife’s behavior. He knows it’s the alcohol, and for a fleeting moment he wonders how he will be able to drive home. It is not so much a matter of falling asleep behind the wheel, or even feeling dizzy or lightheaded. He is simply not meant to drive this evening, to return home, but he will anyway, because he has made the trip before under worse circumstances and influences. He is almost finished with his beer and knows that the time has come for another. He steps outside onto the patio and lifts the lid of the cooler. They are drinking his favorite beer tonight, a grapefruit IPA, which means his friend bought it specifically for him. How nice, he thinks—who would not want to promote this man, who hosts these parties, spends so much money on his friends, and asks for little in return? Only his wife would object, out of envy.

“Maybe we can save this conversation for a different time,” Allen proposes.

“You’re right. Let’s change the subject,” Alice replies.

Alice doesn’t want another baby. She frustrates herself and puts her marriage and friendships on edge for—she can’t identify an immediate purpose. It just seems like the right way to fill the gap, like when she cuts the line at the store because the person in front of her is distracted and won’t notice. She mentioned getting pregnant last week with her husband, just so that they could talk about something. She didn’t see his face as he nodded uneasily, his fingers fumbling with the laces of his sneakers. She picked that moment deliberately so Trevor would have something to think and talk about on his run. She knows he tells Allen all the details of their relationship, the details the way he sees them, those things she would never confide in Jane. She brought up a topic, serious-seeming—a baby—because they have become a couple that remains silent at dinner, allowing their children to explain every thought in their heads, as though the things an eight- and ten-year-old have to say are somehow more meaningful and therefore worthier of conversation. She can’t imagine what gets discussed in the Mitchell house, but they are the more cerebral couple. Allen and Jane both read the same books, watch the same shows, finish each other’s thoughts. Alice isn’t jealous, however. She tries to keep up, but Jane reads too much fiction. Alice sees her mouth in the reflection of her glass, her lips curling upward: the Mitchells read fiction because their lives need to be thrown into relief.

Jane tries to mention a new show that she and Allen are watching, a docuseries about a murder, but she remembers that Trevor does not watch television in the way that they do. He watches basketball and football, at the professional and college level, and sometimes pays attention to the news, because, she assumes, he feels that’s what a person should do. She thinks he could have been a sports announcer, instead of a gym teacher. He has managed to stay fit, and despite filling out in the middle, he has never lost that look of a tight end. She wishes her own husband dressed like a commentator. Allen likes nice things (look at the grill he just bought), but his taste in clothes upsets her. Tonight Alice made a comment about his shirt not matching his jacket, a comment Jane could not disagree with, no matter its rudeness. Next week she will pick out what he wears to dinner when they all go out to celebrate Trevor’s birthday. She should remember to arrange for the babysitter and to buy a gift, one that Allen will suggest. She is not looking forward to the dinner because the Jackson children will be there. They are nine and ten years old, the age when chatting with adults suddenly becomes appealing. She herself just had her second baby a few months ago, and her first two years before that, so she knows her children and the Jacksons’ will not be friends. This is, of course, only true if Alice does not get pregnant again—though, who knows? By then, maybe they will have moved away or found new best friends.

Allen wonders how many beers are left the cooler; he worries that Trevor has had too much to drink. Not too much to drink given his height and weight, but too much to drink to drive home safely. Trevor can be reckless at parties, and if Allen tries to stop him from driving, there will be an argument and Trevor will win. Allen knows that his friend will yell, threaten to wake the neighbors in the houses next door, and that he himself will shake his head and close the front door, disappointed that it should always come to this. When Trevor drinks, he changes into a

different person, no less likeable, possibly more likeable, but altogether different. More abrasive and intrusive. His size becomes apparent, because he becomes physical, harder to overlook. Alice, Allen has noticed, welcomes the difference, encourages it even, perhaps because the drunk Trevor becomes more the man she wishes he were: open and sociable, brutish and assertive. He would never tell that to Jane; he would never give her a reason to dislike Alice. He appreciates their friendship, admires it, because it makes these parties and dinners so much better. In truth, he has never understood how the two women get along. A few years ago he asked Trevor how they would manage with two wives so fundamentally different from each other. Trevor said that women could surprise you.

“Any new crazy students, Mr. Jackson?” Jane asks.

Trevor smiles. He looks at Jane with appreciation, as sincerely as possible, though the beers have relaxed the muscles in his face. No one in the world appreciates his job as a teacher more than she does. At every meal, she asks about the students and the football team. It was Jane who saw when his name appeared in the local paper, who knew when the team had amassed a record number of points for their division, who attended the ceremony when he won an award for coaching. Allen, he admits, also supports him in this way, but for him there is a certain expectation. Jane, as far as he can tell, does not even like sports. She simply cares about him as a friend, as a good person, the kind of person Allen deserves.

Alice refills her glass, disappointed that the bubbles fail to spill over the rim. Does each sip of champagne toast Allen? She digs her feet into the shag carpet and stretches her legs forward. They have been at the Mitchells’ house for almost five hours, and her husband has spoken about school too many times to count. She loves that he is a teacher, that he teaches students how to run, how to hit, how to throw a ball. But it’s not as if Allen has nothing to talk about. Clearly he has stories of his own, stories of success worth celebrating with dinner parties. She does not want to hear about management at his financial firm or about Jane’s work as a hospital administrator, but she knows that either topic is what they should be discussing. She is wearing nice shoes and drinking champagne. School is a topic that she hears about every day from her children. In time, the Mitchells will come to agree with her, when their own children ride the bus each morning. And, she thinks, they will wish they had spent these moments, moments of peace that come too infrequently, talking about something else.

“Did you hear about—I’m sure you know about it—but did you hear about that teacher at Ammons?” asks Allen.

“Oh, you know I hate that stuff,” Jane replies.

“How old did they say the girl was?”

Jane watches Alice purse her lips. This has happened before, though she has never been too sure of the implications. Whenever a school scandal is brought up, Alice tries to redirect the conversation, as though she and Trevor are somehow involved. It must be a fear of Alice’s, Jane thinks, that Trevor will have an affair with a female student and leave her alone to take care of their family. Jane’s own fears are far different. She worries constantly about getting fired, about making an error that makes her look less competent than her peers. She waited weeks before announcing her second pregnancy despite the tightness of her clothes, her more measured gait. It was a silly thing to worry about because there were so many laws to protect her. But, to her disappointment, she has become far more self-conscious in the past year, particularly in the months since giving birth a second time. There has been a change in the way she moves, in the way she handles things, in the way she functions in their little world. She is now more grounded, more stable, but she wants to feel powerful again, carefree, like she can do anything at a moment’s notice. She wants the added weight in her hips to fall away with a single stomp of her foot. “You just don’t want responsibilities,” her mother said. “You’re describing youth, being young.”

Alice tries hard not to think about these school scandals. Trevor would never do such a thing, would never think of doing such a thing, but still she worries. She worries more about what a young girl might say than what an older man might do. Her husband is exactly the kind of teacher that she would have found alluring as a high school student: tall, strong, married with children. Teenagers, she thinks, are not drawn immediately to people or physical features; they are drawn to ideas that lead to mistakes. She has overheard her husband and Allen discussing a teacher they once found attractive, a teacher with whom Trevor now works. The woman is no longer young enough to be the object of students’ fantasies, though Alice has difficulty placing her in an attractive light at any age. It was merely the idea of sleeping with a teacher that had enticed Trevor and Allen twenty years ago. When she closes her eyes, she imagines a young girl, with breasts just large enough to be called breasts, looking at her husband and concocting a simple lie, the type of lie that can end a family, a marriage, your place in the community.

Allen holds Jane’s hand once more, stroking the back of her thumb with his own. Her skin is always softer than his, no matter how much of her moisturizer he borrows. For many years, he assumed that this was a difference between men and women, that men have rough hands and women soft ones. But at work he has met women with hands rougher than his own. He laces his fingers with Jane’s, tucking his thumb inside and stroking the inside of this makeshift pocket, her palm. How much longer will Trevor and Alice stay? He lets go of Jane’s hand and moves his arm slowly, cautiously, to her back, careful not to distract her while she speaks. He makes figure eights against her dress with his forefinger, before dragging his hand up to her neck where he lightly pinches her nape. He hears a lilt in Jane’s voice when he tickles her, though she gives no indication for him to stop. He hopes the Jacksons decide to leave.

“Listen to that thunder!” Trevor says. “The storm is coming after all. Better bring those beers inside.”

“You just want an excuse for another drink,” Alice replies.

“So what?”

“I’ll grab you a lime,” says Jane.

“I’ll help you,” says Allen.

Trevor pulls back the screen door and steps outside. He feels the wind picking up, shaking the vinyl cover of Allen’s new grill. It’s a large grill, sturdy, one that he would like to own himself. He picks up the cooler with both hands, more quickly than he should, and the water inside sloshes over the edge and onto his pants. That’s all right, he thinks. Better than a bottle of wine! He walks back through the screen door and closes it behind him, cradling the container awkwardly in his arms. He realizes that he should drain the water out in the grass, so he opens the screen door once more, steps down the brick steps, and unplugs the white plastic spout. The water rushes out quickly. He tilts the container to let out the final drops. There are two beers left: one for him and one for Allen. They will try to get him to stop drinking, but it’s September. He needs to enjoy these last days of summer. Let him have his fun.

Alice watches Trevor through the window, fumbling with the cooler like a little boy carrying something too big for his body. He has had too much to drink. Here is the proof: this wetness on his pants, so much wetness that in any other circumstance one would assume he poured water on himself intentionally, or even more embarrassing . . . How much longer will they stay? She checks her watch. It is close to midnight; they have been here longer than any other time, longer even than the time when Trevor passed out on the couch. She wonders if her husband drinks because that is what people do at parties like this, or because he needs to. The only test would be for Allen and Jane to have a dinner party every day. Then she could keep track of his behavior with a mental checklist, gauging his interactions with others, his liberal sips of beer.

“Do you think they’ll leave sometime soon?” Allen asks in the kitchen.

“Shh, a minute. I’m listening to the monitor,” says Jane.

“I told you we could have kept the babysitter longer.”

“It was late, and she shouldn’t have to stay just because of them.”<

br />

“Well, what about us? What about, you know?”

Allen reaches over Jane’s shoulder and pulls the monitor from her ear. He wraps his hand around her waist, pulling her body against his own. He feels the warmth between them, the arousal, the end of the night arriving on cue. How many years has he known her? She has had just enough to drink; he knows what comes next. Why has it become so hard to be parents and lovers? There are two babies upstairs, each a part of him, like limbs that ache and stir, parts that keep him from sleeping through the night. He often thinks of how simple they are, how animalistic: they eat, they sleep, they cry. He and Jane have joked about the way kids play in the park, shouting out half commands, falling over, hurting themselves. “They look drunk,” Jane said last week. Allen holds the monitor close to his ear, waiting for the rise and fall of breath. There is always a moment of panic when he or Jane wants to run upstairs or into the next room, but if they wait long enough, the monitor will produce that sign of life, and they will know that all is well. Suddenly he hears music. He lets go of Jane, and they walk toward the living room. Trevor is swaying with Alice, who laughs and tries to keep his big shoes off her bare toes.

“I’m sorry, he said he wanted music!” says Alice.

Jane curls her arm around Allen’s neck. She closes her eyes. This is what the night needed. A little night music! She smiles to herself. They are listening to an album she left in the stereo, an old CD she found at a yard sale. She hears the jazz, the buzz of the woman’s voice, the thrum of fingers against the wooden bass. Caramel, she thinks. Rich, dark sugar swirling in the bottom of a pan. She can almost smell it.

Best Debut Short Stories 2020

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Quotients

Quotients