- Home

- Tracy O'Neill

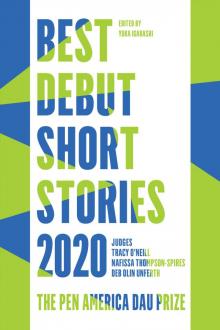

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Page 18

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Read online

Page 18

“I love you,” Allen whispers in her ear.

“Who is singing, Jane?” Alice asks.

“Her name is Etta Jones.”

“Etta James, you mean.”

“No, Etta James sings ‘At Last.’ This is Etta Jones. She’s less known. Here, listen to this.”

Jane pulls away from her husband and picks up the remote from the table. She bites her lip and changes the song. She can’t remember the title or any of the lyrics. She never used to be this aware of alcohol, this conscious of a change in body temperature. She feels little bursts of heat rising under her skin, trapped pockets of warm air that she can’t let out even as she presses against her face. She sees herself drinking, being drunk, as though there are two versions of her, the one changing the music with clicks of the remote and the one thinking of how difficult it is to make these tiny clicks. At what point should she stop drinking? Are there still rules for quantity, even after breastfeeding? No, there are no more rules besides those she sets for herself. She flips through the album, listening to each track for some thirty seconds. Alice sits down on the couch and sighs at the brief disruption in the music. It wouldn’t be a proper party if she didn’t give Alice something to complain about. But she will win this exchange, and the wait will have been worth it. Finally, she finds it. She hears the piano twinkling.

“This one. Listen to this one.”

Trevor has not heard the song before but trusts Jane’s taste in music. She has an ear for this sort of thing, more than Allen or his own wife. They have all gone to the theater before, and Jane is always the one who explains the backstory, why something is important, why they should be more appreciative than they are. She could have been a teacher, Trevor thinks. The song is beautiful; he can hear it now. What a voice this woman—not Etta James—had. He takes another sip of his beer, frowning at its flatness. Alice used to be a singer, he remembers. In college, he met many women who sang in the chorus or onstage, but Alice was different. She sang because she wanted to, not because she needed to be heard and wanted others to listen. She used to sing to their kids; she used to sing, softly, after they had sex and he would play with her hair.

“You’re not gonna join me for this one?” Trevor asks.

“Maybe in a minute. I feel woozy,” Alice answers.

“I won’t leave you like that!” Allen jokes.

Jane sits down on the couch next to Alice, pleased that the song is as lovely as she remembers. She laughs when her husband puts his arm behind Trevor’s back, so that they dance together like a couple. She looks at Alice and catches her smiling. They nod at each other in a silent exchange, a mutual understanding that this closeness between their husbands, formed through childhood, is why they are still up, though it’s already past midnight. Trevor is the bigger man in the embrace, though it’s unclear which of them, if either, is leading. Her husband leans against Trevor for support, a man propped against a wall. Trevor, despite having drunk the most, is now in control. His hand rests on the back of Allen’s head. How funny, Jane thinks, that she has seen him toss her husband into the pool with ease. They are such different sizes, such different people. Her mother once told her to watch out for Trevor Jackson. She would never do such a thing—she isn’t that kind of person. Besides, what would an affair look like, sound like? “Half my patients have had affairs,” her mother told her, “and none of them thought they ever would.” A few years ago, it would have been unthinkable, but now Jane knows that moments do arise when a simple look or remark can mean so much more at thirty-five than it did at twenty-five. At twenty-five, everyone made those remarks, those flirtations, because that was what you did to show the world who you were becoming, who you would become. But now she has lost the ability to hide behind herself. She is a mother. Her first child tells her to sit, to come, to read a book. Alcohol brings back that bygone confidence for an hour until she remembers the truth. It is the exception that proves the rule. She wishes she could live her life two drinks in.

Alice hangs her head over her lap. She hopes that if she pretends to fall asleep, the night will end and she can return home to pay the babysitter, who has earned too much money for a single night. But no one notices her. She looks up at the dancing, if that is the right word. Her husband is whispering in Allen’s ear, probably encouraging him to get to sleep. She knows that her eyes have widened, that her cheeks are stretched upward, that she feels something light inside, as though the night has decided to restart itself. It is the music, the alcohol, the end of a long day. She danced with Trevor for the first time in many months. But why does it feel like one dance can brighten the color of the walls, exaggerate the tickle of champagne bubbles against her upper lip? She loves this feeling, this lightness, more than anything else. Trevor will be thirty-six years old next week. They have been married for ten years, a decade. And, as everyone told her on her wedding day, the years really do start to go by faster. She tells herself not to be so sappy. She knows that wine and champagne have given, only to take away; this kind of happiness is false and short. She has compared it to when she nursed her children, to when they hug her, to when she sees them sing in the choir. Those feelings are the pure thing. Tonight she has danced and laughed under a spell, a cheap magic trick.

“‘Make your mark for your friends to see. But when you need more than company, don’t go to strangers. Come on to me.’ God, I just love that,” says Jane, squeezing Alice’s hand.

“Yes, I heard it. Thank you for playing the song,” Alice replies, smiling.

Allen smells Trevor’s deodorant. It is crisp, wintry, like the middle of a forest. “Just another minute,” he wants to say. The room spins and spins around him, and he looks for his wife. She is across the room, a world away, though he can number the steps between them. He hopes she will not forgo their plans for later. The night and its thunderstorm, music, and conversation have suddenly become too much. He needs to separate the room into segments before he can continue: Alice sits on the couch, smiling to herself, aglow; Jane is next to her, laughing at him and his inability to stand up straight; the music plays over their ears, under their feet; and Trevor, his friend, his brother, holds him because he can no longer hold himself. He tells himself to focus, to count the beats in the music. Why did Alice have to sit down on the couch? He saw the way the Jacksons danced, the way they stumbled together. Don’t give up hope! Suddenly he feels a racing against his skin. It is Trevor’s heart, beating faster than the music, chasing something that will not be outpaced. He worries that Trevor will fall over, but there is no change in their balance. They are still moving, turning in place.

Trevor strokes the back of Allen’s head, brushing against the grain of his hairline. Allen is suddenly very drunk, much drunker than any of them conceived. Trevor realizes that if he steps away, even for a brief pause, Allen will topple over, like a newly felled tree. He remembers the water at the bottom of his shirt, his soaked pants. Surely Allen can feel this dampness against his own clothes. Trevor sways to the music, to the song chosen by Jane, whispering in Allen’s ear whatever words come to mind. In this embrace, Allen is the vulnerable one, the one ready to collapse, the one lost in drunken reverie. There is an intimacy between them, far greater than the one Trevor has imagined during their runs and conversations at dinner. He is so small, Trevor thinks. Like a kid who has come running. Allen says nothing, but Trevor understands that this is merely part of the dance. His heart begins to race, at first arrhythmically to the music, then in double time. He thinks of an agility drill, how his heart punches against his chest the way two cleats shuffle up and down against the ground. Can Allen feel it? They have never been so close to each other. He looks down, but Allen’s eyes are closed, his face clean-shaven and relaxed. He wants his friend to smile, to give some indication that this dance will continue, if not now, then later, when they can acknowledge the current traveling between them, this current they have avoided for years. The music fades. He feels something sink. Tomorrow, he realizes, they will wake

up as though nothing has happened.

Allen waits for the music to restart, but Jane has already turned off the stereo. He feels helpless, naked, though Trevor continues to turn them on the floor. Here is another lull. But no, something has changed. The atmosphere isn’t the same—this is nothing like a quiet lunch. He pushes Trevor away with a nudge, feeling the cushion of flesh against his knuckles. Did that hurt him? But Trevor is a strong man, capable of picking him up and tossing him in the pool. He looks up. Will Trevor retaliate and shove him back, harder, so his head hits the ground with a thud? But his friend has already returned to his beer. Allen raises his chest.

Alice takes the music stopping as an invitation to leave. It seems that Trevor will not notice her many sighs, the glances at her watch, the quiet pleas she makes with her eyes. She rises from her seat and slips back into her shoes. She will offer to drive and her husband will, of course, refuse. Tonight he has behaved differently, and tomorrow it will take time for her to sort everything out. Instead of rowdy, he has been calm, subdued in a way she doesn’t recognize. Maybe it was the mixture of champagne, whiskey, and beer, a cocktail that has tampered with his constitution. Maybe he feels what she felt for that short instant on the couch. She has also seen another side of Allen, the drunk and helpless side. He needs to go lie down and fall asleep. He’s had a long day.

Jane lets the Jacksons out of the house, closing the door behind them with a flick of her wrist and swish of her hair. She turns around and walks back into the living room. Her husband is lying on the couch, staring at the ceiling. She watches his eyes widen and shift back and forth under his glasses. “Look who’s tired now!” she says.

No more after-party fun for them then. It was unlike him to make plans and not follow through, but he, like she, is exhausted. There is always tomorrow for more celebration in the privacy and comfort of their bedroom. It will be Saturday, which means that she will wake up, still early because of her babies, and nap throughout the day whenever she has the chance.

“Good night,” says Jane. “I love you.”

Allen closes his eyes without replying, pretending to be asleep. Those words, simple ones spoken thousands of times per day, are different tonight. Tonight they were whispered by someone else.

Matthew Jeffrey Vegari has published fiction in the Virginia Quarterly Review, Boston Review, and Epiphany. He holds an undergraduate degree in English from Harvard College and a master’s degree in economics and management from the London School of Economics. He is at work on his first novel.

EDITOR’S NOTE

I was drawn to nominate “The Good, Good Men” because of the complex multivalence of Miles and Theo, the way that Shannon was able to give these two brothers a tenderness not often afforded to black male characters. Shannon’s writing, her dialogue especially, felt honest and familiar—not familiar in the sense that I’d heard these voices before, but familiar as if they were kinfolk having a conversation while driving on a road I’ve been down before. I’m always looking for stories that generate more questions than answers, and Shannon’s refusal to provide her reader with a neat/tidy/resolved ending to this family narrative felt exciting for me, and trained my eye to future work from her as a writer. I’m honored that the Puerto del Sol Black Voices Series was a first home for her work, and that PEN America is honoring the story now.

Naima Yael Tokunow

Editor, Black Voices Series

Puerto del Sol

THE GOOD, GOOD MEN

Shannon Sanders

THEO HAD COME all the way from New York with no luggage. From the parking lot Miles watched him spring from the train and weave past the other travelers, sidestepping their children and suitcases with practiced finesse, first of anyone to make it across the steaming platform. His hair was shaved close on the sides, one thick strip left to grow skyward from the crown of his head. In his dark, lean clothing, hands shoved deep in his pockets, he was a long streak of black against the brightly colored crowd. He alone had reached their father’s full height.

He made no eye contact with Miles as he strode to the car and yanked at the door handle, as he folded himself in half and dropped heavily into the passenger seat, releasing a long breath.

“Fucking hot,” he said, pulling the door shut.

Miles threw the car into drive and steered out of the parking lot, out of the knot of station traffic. “Summertime,” he said by way of assent.

These words, the first the brothers had spoken aloud to each other in over a year, hung in the air between them until the car reached the mouth of the highway. Their mother, Lee, had finally moved back out to the suburbs, to the end house in a single-family neighborhood Miles had seen often from the road, all crisscrossed with telephone wires. He was grateful for its proximity, only a four-mile drive from the train station. Last time around, searching for her dumpy apartment deep in the District, he and Theo had lost precious time to gridlock and confounding one-way streets and been beaten there by their sisters, turning the whole operation to chaos. A mess of shifted allegiances and hand-wringing, tears, hysteria. Later, in the relative quiet of Miles’s living room, Theo had complained of his ears ringing.

“No bag, nothing?” asked Miles now, nodding down toward Theo’s empty hands. “We need to stop for a toothbrush?”

“No,” said Theo. “I’m good. I’m out tonight, right after Safeway.”

Miles thought of Lauren back home, washing the guest linens and googling vegan dinner recipes since morning. “Okay,” he said. “Quick trip, though.”

“Just to keep it simple,” said Theo. “We dragged it out last time. A task like that always expands to fill whatever time you allocate for it. You know? We gave it two days, and it took two days. We were inefficient.” He reached for the dashboard and gave the AC knob a hard crank, calling up a blast of chilled air. “This time, two hours. We’ll give it two hours, and we’ll get it done in two hours.”

Miles suppressed a shiver. Stealing a glance at his brother’s outstretched arm, he saw an arc of freshly inked letters at the biceps, disappearing beneath a fitted sleeve. Lauren, who kept aggressive Facebook surveillance of all her in-laws, had kept Miles apprised of each of Theo’s new tattoos for years, undeterred by Miles’s disinterest. Only this last had caught his attention.

“Bad stakeholder analysis, is what it was,” Theo was muttering. “Last time, I mean.”

“What’s the new tattoo?” asked Miles. “The words on your arm?”

Theo blinked at the graceless transition, then obligingly pushed up his sleeve. “Got it in Los Angeles, on a work trip. A girl I was with talked me into it. I had been thinking about this one for years.” He traced his finger around the lettered circle, four words rendered to look like they’d been scrawled on by hand in a familiar chicken scratch. “Miles, Thelonious, Mariolive, Caprice. For us, obviously.”

“But where did you get Daddy’s handwriting to show the tattoo artist?”

Theo let the sleeve drop and folded his arms across his chest. “From a check he sent to the old house for us, with our names in the memo line. I found it in a stack of Lee’s work papers with a bunch of other ones and took it when I went to New York. It was in my wallet when I went on the Los Angeles trip.”

Miles felt a swell of heat despite the frigid air. “You took a check from her and never gave it back?”

“Did you not hear me? It was with a bunch of other ones, and it was about eight years old. All the checks were years and years old, some of them reissues of older ones—he would write that in the memo line. He would send them, and she would put them someplace idiotic like tucked in the finished crossword puzzles or a pile of old magazines. And then I guess lose them, so he had to write new ones. She was always doing that kind of shit with checks. I found this one, and the others, all mixed in with the girls’ old coloring books. I took one and left the others there for her to find never. Is that okay with you?”

Theo’s posture, now, was rigid, his face turned squarely in the dir

ection of Miles’s. Miles took his eyes off the road long enough to stare back, but like a traveler gone too long from his hometown, forgetting its habits and idioms, he had lost his fluency in the quirks of his brother’s face. At one time he had been able to tell, from the slightest twitch of an eyelid, that Theo had been teased past his threshold and was about to burst into tears; to hear an impending temper tantrum in the sharpness of his inhalation. All of that was years ago, when any impulse would buzz between them like a current, felt by one brother even before the other acted on it, when a germ passed to either would invade the other in the blink of an eye. A faraway, definitively ended time. The composition of Theo’s face was the same as always, brooding features assembled slickly under a strong brow. But now it was like their father’s face in the pictures: impassive, all traces of his thoughts as strange and unreadable as hieroglyphics.

LEE HAD A new man, again, this one a fellow patron at the karaoke bar where she’d been throwing away money every week for months. It was known that he mixed good homemade cocktails and spoke a little French, which was probably what had done her in, because he wasn’t particularly good-looking and didn’t seem like anyone’s genius. He had a dog as big as a wolf, supposedly, and for some reason wore too much purple and a signet ring on his little finger.

Miles’s spotty intel had come from Mariolive and Caprice, who, working innocently but in tandem, were only a bit less ineffective than either of them was separately. Lauren, for all her expert stalking efforts, couldn’t find even a single Facebook reference to supplement what little was known about her mother-in-law’s new relationship. It was not known where the new man came from, what he did for a living, or what wives and children lay crumbled in his wake. Nor what in God’s name he was doing making regular appearances at karaoke bars, if not trolling for naïfs like Lee.

Best Debut Short Stories 2020

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Quotients

Quotients