- Home

- Tracy O'Neill

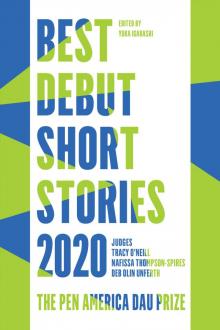

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Page 8

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Read online

Page 8

I am grateful to Barton for bringing this piece to us, as well as for her wonderful translation. I would like to share this from Barton on why she chose to translate this story: “I’m really enamored by the way that Tsumurasan creates a voice and an inner world, and . . . find[s] the interest and the poignancy in very mundane and unremarkable experiences. She doesn’t really stick to what she knows but is often taking elderly men or other surprising characters as her lens onto the world, which I find admirable. I think her dry, understated humor that sort of suffuses her prose is wonderful, and it makes it a total joy to read and translate. Also I’ve lived for a while in rural or semi-rural Japan and I felt the story perfectly evoked the quietness of it, the sense that you could fall off the edge of the next street and nobody would notice, juxtaposed with this sense of a very strong-rooted community—so maybe in a way I related to the narrator’s outsiderness.”

Eleanor Chandler, Managing Editor

Granta

THE WATER TOWER AND THE TURTLE

Kikuko Tsumura

TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE BY POLLY BARTON

THE MOMENT I stepped out of the temple gate, the thick steam wafting over from the building opposite caught in my throat. I knew the source of that steam well enough: udon. The udon manufactory was right in front of the temple where my parents’ graves were.

Tacked up to the wooden wall on the far side of the steam was a recruiting notice. “Experience not required,” it read, which was all well and good, but then it said, “Applicants should be sixty-seven years or younger,” a stipulation whose peculiar specificity bothered me. Sensing a flash of movement, I looked down to the gutter from where the steam was emanating and saw a single udon noodle sliding by. I was quite sure that there used to be more of them in the past. It wasn’t clear to me whether the noodles were being deliberately abandoned, or if they were the casualties of sheer carelessness, but either way the number going to waste seemed to have dwindled over the years.

This narrow street separating the temple from the udon manufactory was on the route I had once taken to school. That was back in my primary school days, a good few decades ago now. Since the death of my mother, my last surviving relative in this town, I came to this area only once every few years to visit the family grave. Each time I returned, I was surprised to see the udon place still going.

Yet I did sense they were cutting back a bit, I thought to myself. Now that I’d started reminiscing about my school days, it struck me that I might as well walk to my old school. I’d left the temple at midday, so I still had plenty of time before the furniture would arrive at my new flat.

Even though there was nothing in particular left for me in this place where I’d grown up, I’d decided to move back. It had all started when a former colleague asked if I knew of any nice, reputable rooms for rent here. His daughter had a thing about natural farming and was interested in moving to this considerably more rural part of the country. I had no leads on any properties whatsoever, but I wanted to be of service if I could, so I’d taken a look online only to discover that the rent for flats in this area was less than half what I was paying at the time. In the end, my colleague’s daughter did not take up natural farming: she stopped leaving her room entirely. Yet I kept thinking about living somewhere for half what I was currently spending, and before I knew it, I’d moved. As a single man living alone who’d retired at the stipulated age, there was really nothing stopping me.

The narrow street that led to where the primary school used to be was just wide enough for a single car to pass through, and I spotted several surnames on the nameplates of houses that brought vague memories of old schoolmates floating to the surface of my mind, but all these names were common to the region, and it was likely that the houses belonged to different people entirely. Not only did I have no relatives here, but it was safe to say I didn’t really know anybody in this town at all.

The streets were so quiet. In the city, you’d often catch sight of birds, but their song would be drowned out by the noise of the passing cars. In these streets of my hometown, all I could hear were my own footsteps, and the cries of the sparrows, and some caged bird kept in one of the nearby houses.

It came to me that if I turned down a certain side street, I’d get to the sushi restaurant my parents sometimes got takeaways from on special occasions, but I figured that if I attempted a visit I’d likely only end up lost, so I stuck to the route I knew. Had that restaurant managed to weather these forty-something years? Probably, I guessed, so long as there’d been someone to take over from the sushi master who was there when I was young.

My old school was still there. Not the wooden building I’d been familiar with, of course, but from what I could see, the concrete one that had replaced it was pretty similar in layout to the original. I had no idea when the reconstruction had taken place. Even this concrete number was showing signs of wear and tear. Between the gates and the entrance was a small hut-like structure, with a sign pinned to it that read LOCAL RESIDENTS’ PROTECTION SQUAD. Could I join? I wondered. Would the squad accept members without children or grandchildren?

I didn’t really feel any deep emotion towards the school, beyond a sense of satisfaction at having seen it again, but when I glanced down the little alley diagonally across from the gates and glimpsed the sea in the distance, I gulped. Now I remembered. This was the same alley I’d gazed down on my way back from school, and at its end, the same sea.

I stood there in the middle of the crossroads for a while, staring out at the strip of sea floating at the end of the alley. Eventually, an approaching car honked its horn ostentatiously at me and snapped me back into reality, and I set off back along the road I’d come down.

Walking towards the town’s little train station, served not by the public network but a private line, I started to worry about how few amenities there were around here. How did people get by with just one convenience store? Of course I myself had once coped. But I wanted to know if the convenience store could be relied on, so I went inside and roamed up and down the aisles. Being in the country, I’d feared its selection might be limited, but I soon realized that it was a standard convenience store with the standard array of goods, which comforted me a bit. There was a decent selection of magazines and a range of cheap DVDs, too. I’ve recently moved to this area, I said to a cashier with a bun and oversized glasses. Where can I go to buy the kinds of books that you don’t stock here? Or household tools and that sort of thing?

If you go onto the highway, she informed me politely, there’s a big chain bookstore and a home store, and a supermarket as well.

As I pictured the location of my new home in my head, it came to me that the block of flats could be accessed from the highway, and I decided to switch my route so I could investigate.

As the shop assistant had promised, beside the four-lane national road was a large bookshop shaped like a big block of tofu, a rectangular two-story home store painted a dull shade of blue, and, beside it, a one-story supermarket that seemed pretty spacious. They looked rather out of place in this area, where all the other buildings were so diminutive and flat. Perhaps as the result of some kind of financial arrangement, the supermarket and the home store shared a car park, which had a fast-food chain and an all-you-can-eat Korean barbeque restaurant perched in the corner.

Otherwise, there was basically nothing there. Lining the sides of the highway with its meager scattering of cars were fields, houses, a great big billboard advertising termite extermination, a great big billboard advertising a cash loan hotline, a great big billboard advertising flats for sale, and so on. All the billboards were noticeably enormous. That was proof of how much space there was in this part of the country. Had the house I’d grown up in had a termite problem? I wondered about this as I walked down one side of the highway, pulling out my smartphone to check my whereabouts on the map before turning down the road that led to the coast, where my new flat was. Now that I was getting farther from the station there seem

ed to be more fields around. Not as many as when I’d been growing up, for sure, but the fact that at least half of them had survived came as a shock.

I walked along the side of an onion field facing the highway, heading for the ground floor of the two-story block midway down the road to the sea. Going by rent alone, there was no end of flats in the area that I could have selected, and my sole reason for choosing this one over any of the others was that it was near the house I’d grown up in. And yet when I arrived, I saw that the place as it existed in my memory didn’t quite match up with the place as it actually was. Cocking my head in bemusement, I stuck the key that the estate agent had given me into the keyhole.

There’d been a water tower, it came to me suddenly. I couldn’t for the life of me remember where, but it was somewhere around here. In the middle of a field, perhaps, or standing in the grounds of somebody’s house. It had been a lovely shade of—I don’t know if you would call it cyan or pale aqua or what—but in any case it was a beautiful shade of light greenish blue, and there was something about the grandeur of its presence, how it stood taller even than the school, which had captivated me. Whenever I played around with friends outside, I’d steal glances in its direction when they weren’t looking. The truth is, I didn’t know it was a water tower until later, once I’d grown up. It was with the vague notion that I wanted to build things like that tower that I found myself a job at a construction company with strong connections to the water industry.

I opened the door to my flat and was just about to step inside when I heard a voice at my back.

Um, excuse me? said the voice. It belonged to a middle-aged woman with a surly expression who looked to be just a few years younger than I was. I’m the caretaker here, she said, and, pointing towards the garage, went on: A parcel’s arrived for you. Will you deal with it please?

I looked in the direction she indicated, and sure enough I saw the box that she meant: not that deep, but of considerable height and width. I made out the name of the company printed on the box, and hurried towards it, my heart fluttering a little.

The cross bike I’d ordered online had arrived early. She could have sent the courier away, the caretaker told me, but he’d begged her not to make him redeliver such a big parcel, and because she knew the person who ran the company, she’d agreed to sign for it on my behalf.

This really is the countryside, I thought to myself as I listened to her story. When you know the person who runs the delivery company, you know you’re in the countryside.

I’d be grateful if you opened it right away, she said, and before I could really think, I was saying, Then I’d be grateful if you lent me a box cutter.

She retreated into her room and emerged with a barber’s razor saying, This’ll do, won’t it?

The large, flat cardboard parcel was bound together with huge copper staples, and it took some doing to get it open.

What is that thing, anyway? asked the caretaker, coming up behind me.

It’s a bike, I answered.

Why would you go and order something like that? she asked as she mounted the enormous piece of discarded cardboard and folded it in half. That didn’t make it much less bulky, though, so I scored some slits into it with the razor, and somehow managed to fold it into smaller pieces.

Someone I knew from my previous workplace took up cycling and he gave me the idea, I told her. He was always saying how much he enjoyed it.

As I spoke, I recalled the conversation we’d had at my leaving party. The guy in question was younger than I was but still past forty, and after being diagnosed with hyperlipidemia, he told me, he’d taken up exercise.

You’re a strange one, you are, the caretaker said, shaking her head as she picked up the strips of bubble wrap that had been encasing the bicycle, winding them round and round into a ball. The person living in your flat before you was a strange one too. And she lived on her own, like you.

I couldn’t figure out if the caretaker was a real busybody or if she just had a lot of spare time on her hands, but either way, she stood there chatting away as I divested my bicycle of its myriad pieces of packaging.

She was an elderly woman, the caretaker went on, by the name of Noyo. See, even her name was strange! Apparently she’d been in love with some childhood friend of hers. He was a few years older than she was, but he went off to war and never came back and she refused to marry anyone else. She worked selling insurance, made it as far as the head of the branch, if memory serves me right.

Noyo had moved to the area after retiring, the caretaker went on to say, and found herself a job in the clothes alterations kiosk at the local supermarket, where she’d worked right up until the day she died of heart failure. Before Noyo’s death, the caretaker had been wary of her, figuring that she was exactly the type of person to die unnoticed in her flat and go undiscovered for months. In the end, the person to find her body was a young colleague of hers from the alterations kiosk.

Noyo, it turned out, had forever been telling people at work that if she ever failed to turn up to the kiosk without giving any notice, they were to go over to check on her. She would always inform them if she couldn’t make it into work, and had taught herself how to use a mobile phone in the case of an emergency. When Noyo hadn’t come in one day, a colleague had tried to call her, but Noyo hadn’t picked up. So I just came over, the young woman had said with a shrug.

Noyo’s will had been easy to find, and disposing of her personal affairs was simple enough. She’d instructed that half of her money should go to distant relatives living in another part of the country, and the other half to the closest orphanage.

The caretaker spoke in such detail that I had to wonder if she should be revealing so much to me, given I’d never even met this person, but I supposed she’d decided that it was all right, since the subject in question was dead and had no close relatives. As it happened, I already knew from the estate agent that the previous tenant had passed away in the flat. Would the caretaker talk about me in the same way to the next person, if something happened to me? Well, I thought, so be it.

The only thing is, the caretaker went on, she had this pet turtle, which has proved a real headache. She only got it a couple of months before she died, see, so it wasn’t mentioned in the will. I’m keeping it in my room for the moment. Would you like to see it?

But knowing that my furniture would be arriving at any moment, and that afterwards I wanted to take my cross bike for a spin, I declined and said I’d leave the turtle-viewing for another time.

Before you go, there’s something I want to ask you, the caretaker said, folding her arms across her chest and looking straight at me. How is it that people like Noyo and you can stand to be all on your own?

I looked down at the caretaker’s left hand, verifying the presence of a ring on her wedding finger, and then shrugged. I guess I’ve always been busy, I said.

But there are plenty of busy people who aren’t single, the caretaker replied.

I was busy and I was never very good at any of that stuff, I said, and then I walked into my room cradling large amounts of cardboard and packaging.

As I consigned the rubbish to the corner of the kitchen, my mind traced its way along the path that had led me to where I was now, the path I so rarely thought of. I realized soon enough that there was a reason that I so rarely thought of it, and stopped—though not before I’d had time to recall the woman of twenty-eight my boss had introduced me to back when I was the same age, who’d said I was “too vacant.” And the woman five years younger than me I’d been intending to marry at thirty-five, who had turned out to already be married, and had returned in the end to her emotionally blackmailing husband. And the woman ten years younger who I’d met at forty-five, who’d broken it off because of her concern about the perils of childbirth. At work, I’d found myself being sent all around the country in place of the married folk whose families prevented them from being posted to far-flung places, and occasionally I would get friendly with wom

en in one of those various locations, but usually, whenever it looked like things might be going somewhere, I’d be called back to head office.

It wasn’t that I wanted to stay single and carefree. Somehow things never quite went my way, and I wasn’t ever able to plunge myself headlong into anything. I regret that, I really do. The reason that people need family and children is that without duty, life just feels long and flat. The simple repetitiveness becomes too much to bear.

But those thoughts vanished into the ether with the arrival of the moving company. The furniture they’d brought from my previous flat consisted of a fridge, a washing machine, a futon, a single chair, and two storage boxes for clothes. Everything else I planned to order online.

You must have a sea view from out there, the youngest-looking of the movers said, pointing to a back-room window whose storm shutters were still down.

By the time I collected myself and replied, Oh really? the kid had already finished putting on his shoes in the entranceway.

I decided to leave the furniture and the sea for the moment and went back down into the garage to mess around with the cross bike. A clear plastic pouch housed the instruction manual and an Allen key, which I gathered was used to turn the handlebars, which had been rotated to one side in order to fit the bike in the box, as well as to adjust the height of the saddle and so on. I stood to the left of the bicycle as I adjusted the angle of the handlebars, closing each eye in turn, blinking several times, and tilting my body from side to side to check that they were really straight. According to the manual, the part between the handlebars and the frame I’d been adjusting was called the “stem.” I’d learned something, I thought to myself.

I went back to my room to pick up my rucksack, packed it with my wallet and the new chain lock that I’d ordered online along with the bike, and set out. Compared to the city bikes I’d ridden before, the “top tube”—another new word from the manual—was much higher, and I had a hard time straddling it and perching on the saddle. After a while I realized that I needed to place my feet on the pedals before trying to sit down. Once I’d figured that out, I managed to set forth in relative comfort, pitching gently from side to side as I went.

Best Debut Short Stories 2020

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Quotients

Quotients