- Home

- Tracy O'Neill

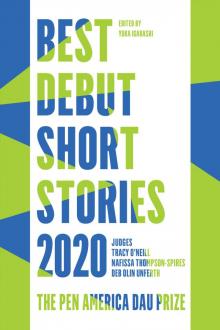

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Page 9

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Read online

Page 9

Beer, beer, beer, sounded the voice inside my head. My body felt lighter. A bike is not like a car. On a bike you feel the speed right there on your skin.

Under a gazebo in the corner of a field was an unmanned stall selling homemade pickles. Unable to resist, I stopped my bike and bought a bag of pickled aubergines and a whole pickled daikon. The money went into a small square wooden box at the side of the stall.

Then I set off in the direction of the supermarket once again, the beer, beer, beer chant growing ever stronger. There were very few bikes in the rack. My gaze was drawn to the abnormally chunky blue mountain bike chained up to one side, and I found myself pulling in alongside it. My bike was also blue, as it happened, but compared to that mountain bike it looked like a little boy’s. The round white-on-black logo didn’t help.

The chorus of beer, beer, beer was now so commanding I couldn’t think of anything else. Inside the supermarket I made a beeline for the alcohol section, picked up a well-chilled six-pack of amber Yebisu, marched over to the till, and left.

I’m forgetting something, I thought, cocking my head, but of late I’d given up hating myself for being unable to remember things, and so I simply told myself that whatever it was, I’d come back for it when I remembered. With that, I made my way to the bike rack, where I came across the owner of the mountain bike studiously removing the chain and the other bits of his lock. He was kitted out even more seriously than I’d envisaged: a black helmet, black sunglasses, and a black Lycra outfit. As I stood watching him, whistling internally in awe, the petite, wiry-looking man raised his tanned face. He was almost certainly older than I was, I saw, the kind of age that made him unequivocally an old man. With his long gray-streaked hair tied at his neck and his sunglasses, there was something pretty intimidating about him.

Thinking it wouldn’t do to keep ogling him, I averted my eyes, just as he said, That’s a great bike you’ve got!

Oh no, I said, taken aback. No, it’s nothing on yours, this is just a cross bike I bought for fifty thousand yen online, it’s not a patch on what you’ve got there, I said, indicating his mountain bike sheepishly.

A cross bike is perfect for this area, though, he said. The roads are really not in great condition.

He had a slight accent—it sounded as if he was from the south, maybe Kyūshū. The accent went a long way to soften the ridiculously professional look created by his cycle gear.

At first I was planning to get a road bike, I said, but I thought I’d try this out for a year and see how it goes.

I used to ride a road bike too, he said, but the roads here are surprisingly uneven and I was forever getting punctures. That’s why I switched over to this one, but now the rear hub is quite heavy, and I get tired quickly.

Right, I said, though in my head I was thinking: rear hub, you say? I resolved to look up what that was when I got home.

I’ll see you around, the man said, raising a hand and cycling away. He cut a dashing figure, that was for sure. I stood watching him until he left the car park, then zipped the six-pack into my rucksack and cycled back along the highway to my new home.

Dusk was falling. I had the faint sense that it came earlier here than in the flat I was living in before. My head was a lot clearer now that I’d bought the beer, and I recalled something else I’d meant to buy: turtle food. There was another thing as well, though, which I still couldn’t remember.

I parked my bike in the rack for the block of flats, and pressed the buzzer for the caretaker.

I’ll take the turtle, I told her when she emerged.

Oh, will you? she said, nodding blankly, and then came out carrying the small tank. I’ve got a box of food, she told me, so I’ll bring that round later. But what made you decide to take it?

This woman questions everything, I thought to myself. In a flash of inspiration, I said that I’d seen Aki Takejo talking about keeping turtles on some TV program a while back and had been wanting one ever since.

Hah. The caretaker laughed darkly.

Back inside my room, I unzipped my rucksack and took out the Yebisu and the bagged pickles.

Ah! I exclaimed, striking myself on the forehead. I should have bought kitchen stuff.

Setting one can of beer and the aubergine pickles aside, I transferred my shopping of the stuff to the fridge. I rinsed my hands, put the pickles and the beer on my chair, which I carried into the back room, and then opened the storm shutters. Just as the guy from the moving company had said, there was indeed a sea view from the balcony. The sea was mottled with the light of the setting sun.

I carried the turtle tank out onto the balcony, washed my hands again, and took the beer and the bag of pickled aubergine off the chair. I’d been planning to take the chair into the back room and drink the beer there, but I decided to move it out onto the balcony instead.

Outside, the sea moved a little closer. I breathed in. The smell! There were probably too many impurities mixed in to really call it the smell of the sea, but it still seemed to me like the same smell I’d breathed as a kid.

And there in the distance, to one side of the balcony, was the water tower I’d been looking for. It was curious that I hadn’t been able to see it from the highway, but I supposed these flats must have blocked it from view. There it stood in the middle of the field, delicately assembled of slender metal bones. There was an onion-drying shed nearby, and a wooden gazebo, which I guessed the farmers used as a resting spot.

I popped the tab on the can of beer and raised it to my lips. It tasted so good, it was as if all the cells in my body trembled in appreciation.

I’ve come home, I thought. Home to this scenery, to all these things I used to look at.

As I raised the beer to my lips a second time, the turtle in the tank moved, and I heard a faint scrape of gravel. The only other sound was that of the wind blowing.

I opened up the bag and took a bite of one of the pickled aubergines. Then I remembered the other thing I’d forgotten to get. Résumé templates, so I could apply for the job at the udon manufactory in front of the temple.

Tomorrow, I decided, I’d go to the supermarket and buy the templates. I’d cycle there—in the morning this time. I was pretty sure that would feel great.

Kikuko Tsumura was born in Osaka, Japan, where she still lives today. She has won numerous Japanese literary awards, including the Akutagawa Prize for her book Potosuraimu no fune (The Pothos Lime Boat) and the Noma Literary New Face Prize. “The Water Tower and the Turtle” is her first story to appear in English. Her first novel in English, There’s No Such Thing as an Easy Job, is forthcoming from Bloomsbury.

Polly Barton is a translator of Japanese literature and nonfiction, currently based in Bristol, U.K. Her book-length translations include Friendship for Grown-Ups by Nao-Cola Yamazaki, Mikumari by Misumi Kubo, and Spring Garden by Tomoka Shibasaki. She has translated short stories for Words Without Borders, The White Review, and Granta. After being awarded the 2019 Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize, she is currently working on a nonfiction book entitled Fifty Sounds.

EDITOR’S NOTE

What we first found exciting about Willa C. Richards’s “Failure to Thrive” was its ambitious use of physicality. The sensory details are visceral, with an economy and a cadence that my colleagues and I could not let go. Everything in this story feels vivid and fully inhabited—the chilly apartment with its sputtering heat, the clammy skin of an ailing mother, the heft of a skull in her hand, the pool water lapping at her body. But that is only the first layer of Richards’s ambitious work. Beyond exterior sensation is a more abstract and nuanced exploration of physical being. Richards is interested in the most intimate realities of a human body—not just its condition but one body’s desire for or aversion to another, one body’s need for another, the remains of bodies from long ago, and the future growth of one small human; she explores this in a way that is detailed and precise, but never either clinical or gratuitous. A third layer, the psychological examination of a tatt

ered relationship, takes place in the tight proximity of a shared blanket, across a diner’s booth, in the confines of a compact car blocked in by thundersnow. With a command and poise that would be remarkable for any writer, not just one making her debut publication, Richards brings her characters and their environment together to create a truly unforgettable, unshakeable story.

Emily Nemens, Editor

The Paris Review

FAILURE TO THRIVE

Willa C. Richards

ALICE READ JOHN Mark’s letter, her eyes narrowed, as I paced our tiny apartment. The envelope contained instructions for retrieving two sets of human remains from the University of Florida. I sometimes worked for John Mark, the director of the Milwaukee Public Museum, in exchange for modest paychecks and access to the museum’s research collection. I often did the jobs the museum interns refused to do, like retrieving artifacts originally accessioned by the MPM from other institutions and bringing them back to Milwaukee. I hadn’t taken one of these jobs since before Tess was born, afraid to leave her or Alice, but we were so poor we had begun to eat only the casseroles Alice’s mother sent over in weekly batches.

Alice tossed the letter on the coffee table. She wiped a bead of sweat from her forehead. I thought about how sweaty she used to get after her long runs up and down the Beerline. How good her skin tasted. I couldn’t remember the last time she’d gone running.

“So you want to go?”

“I don’t,” she said.

“I’ll drop you at your mother’s, then.”

Alice’s mother refused to speak to me because we’d had Tess out of wedlock. Once, she’d called the apartment, and when I picked up the phone, she whispered, You’re my penance, William. She loved Tess, it was obvious, but she acted as if Alice were a single mother. Their relationship had become fraught.

“Like hell you will,” Alice said.

I threw my hands up. “What then? We need this money.”

“Shush,” Alice whispered. “You’ll wake her.” She was right; Tess began then to make low, wet noises from the other room.

I went to get her but Alice said, “She’s fine.” She wanted Tess to learn to calm herself down. Were babies even capable of that kind of thing?

The windows let too much of the winter into the old apartment. To compensate, we had two space heaters near our orange couch and an electric blanket under which Alice was hunkering. She looked highly flammable. The cold crept up through my sock feet and I started shivering, so I went to the couch and Alice held the blanket up for me to come underneath with her. Even though she kept a whole cushion between us, I was grateful. It reinvigorated my efforts.

“Come with,” I whispered.

“Fine,” she said. “I’m sick of being here anyway.”

“Where?”

She gestured around. The space heaters hummed incriminatingly.

“This crappy apartment. Milwaukee.”

“A trip will be good for us,” I said. “We can see the ocean, maybe even some mountains on the way?”

She shrugged and I felt a surge of hope.

“Even if we leave, we’re still stuck here.”

I cringed but said nothing. Though we’d both been born in Wisconsin, I knew Alice had always dreamed of living in some ocean-side city where the weather was less hostile, or at least more predictable. She said she wanted sunshine every day. But then we had Tess, the progress on my dissertation slowed to a halt, and Alice put school on hold indefinitely. Sometimes I was scared she was right; maybe we were stuck.

The lights flickered and went out. Snow on the power lines. I wanted to kiss Alice in the dark, but I sat on my hands. Tess’s cries turned into sobs. The lights came back on. Alice went into the bedroom and brought Tess with her to the couch. She tucked herself back under the blanket and pulled the wide neck of her shirt down so her breasts fell out. Alice grimaced as the baby took a nipple in her mouth. I knew they were sore: Alice rubbed cream on them at night. I missed my own mouth, my own tongue around them. She used to let me feel their raised edges with my fingertips, which made her moan. I had no conception of the line between what felt good and what hurt. I reached for her. The building was quiet except for the sound of water rushing through the pipes.

“Stop,” Alice said.

I thought about some of our early sex, when we’d first started dating. Once I’d playfully swatted at her face and pressed her right cheekbone hard into the bed with my palm so she couldn’t turn her head or look at me. She said, Hit me, and I’d slapped her so it made a sick noise. When her face bloomed with my handprint, I got harder inside her, and I was seized by a rush of guilt.

“Okay,” I said, and sat on my hands again.

The lights went off again and the radiator gasped. Tess fell asleep with the nipple still in her mouth and I watched Alice fight sleep, her head lolling back on the couch, her shirt pulled low, the darkness filling in her collarbone and the hollow spaces of her throat.

TESS SCREAMED. SHE woke every two hours. Did she hate the world already? Did she miss the womb? Did she hate me? Alice said babies just screamed. This was normal. This was natural. I was learning how to do things in the dark. I was learning how to do things in my sleep. I pulled the baby away from Alice and her eyes stayed closed, but I knew she wasn’t sleeping. Sometimes we let each other lie about that sort of thing. She looked vulnerable with her breasts out and Tess gone from her chest. The winter sky was heavy with purple light and it flooded the apartment, shadowed Alice, bruised her body. I changed Tess in the dark and put her back on Alice and Alice held our baby as if I’d never taken her, as if she’d been there all along.

TESS WAS A breech baby. She was also a very large baby, which the doctors informed us was an affliction, one they called fetal macrosomia. I had scrawled these words, the question of them—fetal macrosomia?—in my field notebook with the hopes of determining their full meaning later. I sometimes did this with potsherds without proveniences, too. Alice ignored the words. She disliked her doctors, all of whom were young men, and she only barely trusted our midwife.

The contractions forced Tess against Alice’s pelvic bones for twelve hours until the midwife could turn her. The doctors said Alice would need an episiotomy, a procedure they described as mostly a preventive measure. They made a surgical cut in Alice’s vagina in anticipation of tearing. This seemed to me emblematic of medicine in general; doctors were always trying to do the body’s work themselves. The cut ruptured and became a third-degree tear. Tess was born faceup and Alice received twenty-two stitches. The midwife said it was normal to tear, natural, but she conceded that twenty-two was a lot.

At one point, during a particularly painful contraction, Alice swung her legs over the side of the hospital bed and kicked me in the shin. She said she wanted to break my nose. I said okay and let her punch me, and though she did not break my nose, it bled. When I leaned over her in the hospital bed to kiss her temple, she wiped some of my blood away with the back of her hand. In the weeks after Tess was born, I thought of this moment often.

WE LEFT FOR Florida as soon as the streets were clear and salted. Alice stared out the window and Tess screamed. When I couldn’t drive anymore I stopped at a Big Boy in southern Indiana. Alice was pretending to sleep with her head against the window and I shook her shoulder. She threw my hand off.

“I’ll stay in the car,” she said.

“No. Come eat.”

I got out and grabbed Tess, still in her car seat, from the back. I swung the car seat between my legs, a motion that had calmed her before. But when I swung the seat forward she flew out of it, and her body was in the air for an interminably long time before she fell into a deep snowbank. I stood for a second and then rushed to her. She made no noise and her eyes were wide as though she might even smile. I picked her up and held her to me, brushing the snow off her snowsuit. I kissed her tiny nose. I said, “Sorry, sorry,” though it struck me as something you say to an adult, someone who understands regret. Alice got out of t

he car.

“Why didn’t you buckle her into the seat?” I asked.

“Why didn’t you?”

I wanted to put my hands on her. Instead I held Tess tighter.

The restaurant was sticky—the linoleum floors, the plastic tablecloths, the menus. I had to peel myself off everything I touched. I ordered the buffet for both of us and made up a plate of eggs and bacon and waffles for Alice, even though I knew she’d barely touch it. She’d had almost no appetite since Tess was born and I’d watched her shrink, burning thousands of calories nursing but barely eating.

Alice picked at her food until Tess started crying again. I knew Tess was probably hungry by now and I tried to finish eating but I felt the whole restaurant watching us. Tess cried and we left her in her seat, each waiting for the other to pick her up. People stared. Alice put her head down on the table.

I HAD THOUGHT the warm air and the change of scenery might cheer Alice, but the farther south we went, the more deflated she became. We stopped that night in Chattanooga, and even though I pointed out the smoky silhouettes of the Appalachian foothills outside our hotel window, she called the city a total dump. We left early the next morning, and by the time we got to Gainesville she looked withered. The hair at the back of her neck was damp. I rolled the windows down and she rolled them back up again.

I dropped the girls off at the motel and went to pick up the bones. The skeletons were housed in the anthropology department, which was in the social sciences building, a structure that looked as if it had been built with a nuclear holocaust in mind.

Best Debut Short Stories 2020

Best Debut Short Stories 2020 Quotients

Quotients